In episode 238 we meet Juli Rush who is an Educator, Foresight Strategist and a Death Doula with a focus on partnering futures + death and grief processing.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

Resources

Article: When the Future Dies: Hospice, Vigil, Compost by Juli Rush

Website: https://www.whenthefuturedies.com/

Upcoming SXSW March 2026 Talk, When the Future Dies: Ritualizing Grief & Joy

Instagram: @whenthefuturedies

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/juli-allen-rush-whenthefuturedies

Other references:

Transcript

Peter Hayward: Is there a cost to convenience? What is the relationship between friction in our lives and our sense of self?

Juli Rush: There's been a lot of talk lately about that we have gone frictionless. That we are building frictionless societies where there's no rub anymore. And how that is connected to the loneliness epidemic, that when we never have to rub up against anything hard, we find ourselves more lonely than ever.

And I think all those things certainly are linked in a part of the greater system, but I think this frictionless conversation that folks are now going analog again, where we want to touch the world around us. And I think all of that will be a part of feeling our feelings and spending time to get present to that.

Peter Hayward: That is my guest today on FuturePod. Juli Rush is an educator and administrator in Houston, Texas. She is also a certified death doula and foresight strategist, with a focus on partnering futures + death and grief processing.

Welcome to FuturePod, Juli Rush.

Juli Rush: Thank you, Peter. Honored to be here. Excited to chat.

Peter Hayward: Yes. So am I. So Juli, if you know the drill, we start with the question: the story question. So what's the Juli Rush story? How did you get involved with the Futures and Foresight community?

Juli Rush: Yeah, thanks.

So, I was on Twitter back when it was called Twitter and nd I saw someone call themselves a “futurologist”, and I had never heard that term. And so I immediately was curious and looked it up and said, “that sounds very neat. How does one become a futurologist”? And fell down a rabbit hole.

And I live about 10 minutes from the U of H campus, the University of Houston, and saw that they've got a great program there. I had been thinking about continuing ed. I had done my undergrad in sociology and theology and knew I wanted to go back to school. I'm an educator. I'm an administrator, and I work in education, and I knew I wanted to go back to school, and I thought that sounds really fun.

Why don't I try out this foresight thing, see if I like it, and we'll go from there. And then came covid and it rocked everybody. And I happened to really love the community and was able to really get involved there. And now I teach for the university-I teach in the program-and and have been able to serve on project teams and do some writing and traveling with the students. Andit has just been a really beautiful experience and match a lot of what I had already been doing, ike a lot of us, I think, who come to futures and foresight, you're already probably a system thinker. You're already the one in the group that's asking “why” “how might we do it better”? And and just fell in love with it.

Peter Hayward: Yeah, I used to say, Juli, I used to, I both felt it when I found the classroom in Australia, and I saw it then for 15 years when I taught it, people came home without knowing they'd been away.

Peter Hayward: The beautiful thing to see where people who possibly felt they were on the outside of something suddenly found their tribe.

Juli Rush: Yeah, exactly. We’ve just started a new semester, and with the Intro students we start the first class with “please introduce yourselves to each other in small groups, and don't read your resume.Just tell each other where you're from, how you came to us, and then what do you value”? Because several people don't get to do in their life don't get paid to always do what we value. And so I give them the opportunity. Undoubtedly, we talk about what we do professionally for sure, ut we start with that question of “what do you value”? because I think that's what lends itself to the entire program is to say: We're gonna teach you Framework Foresight at U of H. We're gonna teach you who some giant thinkers are in the field. We're gonna have you listen to FuturePod. You're gonna write us several essays about FuturePod and listen to some really fine folks.

And then at the end of all this, you're gonna have to figure out what to do with this. And our hope is that you take those values and you layer it, you enmesh it, you find ways to bring yourself to life. And your uniqueness in this field is what makes us really thrive. And you're absolutely right, I think a lot of people feel at first kind of intimidated. It's a brand new concept to so many people, and they feel a bit nervous. And I'll say, “if you're here, you're meant to be here”.

Peter Hayward: Yeah.

Juli Rush: And we're gonna find a way to shine some light on you and on how you might work with the tools and frameworks and all the things we're gonna give you.

Peter Hayward: So what's unique about Juli and Futures?

Juli Rush: Yeah. So it's just-it's a sad story-but I, when I was in the Foresight program, I was also finishing a certification and a training to become a death doula. And so similar as a birth doula, you're helping people on the other end. Some people are really familiar with that term, and some have not heard of that.

I was finishing that and also finishing a grad certificate in thanatology, the study of death and dying, which is just around the non-medical side, right? Emotional, psychological, philosophical, theological, and was wrapping those up. And I remember working on projects for UH and seeing this moment when we would go and speak to a client, and I'll often say, this could be a friend, this could be a partner, this could be anybody, but you have this moment where you're sharing this information about the future and you'vedone all this beautiful research.

For us it's beautiful scenarios and you've gone through all the pieces, and you're telling someone, “Hey, I have some things to give you”. And there's this moment of shock, right? Like very much Toffler’s, Future Shock moment of “wow”, overwhelm, and grief. And it smelled, and it tasted, and it felt so similar to the other work that I was doing.

I just sawthis ability, this skillset to sit with people in those moments. And the reason I got into the death space was because in 2017 my younger sister passed away of cancer. he was diagnosed at 29 and died at 30. And that was not expected. I had to decide in that moment who I wanted to be in my systems and in the future.

So what I started to work on was how we grieve futures death or how we grieve the future because it's often not about looking back, it's about looking forward and deciding who I have to be to move forward with the new information. And so whether I'm doing a consulting project or whether I'm sitting in a futurist or foresight strategist capacity, or I'm sitting in classrooms and working with Gen Alpha. Iemploy, depending on the time of year, between 20 and 100 Gen Zers and so they're mid twenties and they're struggling right now. That is an age group that's struggling with the wide world they're walking into. And so just noticed It's sitting with parents, it's sitting with friends, you can just use those skill sets so easily together.

So I started to write some articles, started to work on some frameworks, and started to do some speaking around that. And it just seems like folks are, I think post COVID, they're either really ready to talk about it-talk about grief and all the ways that we grieve all the changes and transitions-or they don't wanna talk about it at all. And so being able to help folks navigate that space became really important to me.

Peter Hayward:t is.You've already coined the phrase “Future Shock”, which of course we all know was a classic book that talked about shaking our certainty that even what was coming was actually unimaginable. And Toffler’s book really hit a point in the seventies that it became, “yes, that's what we're going through”. You are, and not just you, but you are talking about grief. So, tease apart or weave together the idea of “shock” or just change, and this idea of what it is to grieve.

Juli Rush: Sure. I am lucky. The school that I'm an admin and a teacher for is right outside the Houston Medical Center. and a lot of our parents are doctors, and I get to spend a lot of time with neuroscientists and therapists and get to talk to them about, “tell me what's happening to the body when we go through these moments of shock and tell me what's happening, not just psychologically and how we think of these things, but when the body is experiencing shock. I think for a lot of people when you look at either the stages of grief-we have some really beautiful writing that has come out of the grief space-first we move through denial. And now we've added on different layers too. There's no longer five stages. We've added on more. I think shock is that beginning moment of, “oh wow, this might be changing for me. This might be happening”, and we get paralyzed. I think for a lot of people, (there's so much terminology now), whether you call it “functional freeze” or you call it “intellectualization”, there's lots of terms for it, but a lot of people are moving through this shock that turns into this freeze, and they don't actually let themselves experience grief.

They will move forward physically-their bodies are moving forward, their lives are moving forward, but they don't actually pause. And I know working with kids, we do a lot of research on how much safety does a person need to experience to be able to feel emotion. And I think that shock is one of those-is it actually an emotion r is it just something that's happening in the body, and do we name it? So I think all those things layer together. And I remember whenever I read Future Shock-I taught a psychology class for U of H“Psychology of Futures” class as an elective-nd we actually start the very first class reading the first chapter of Toffler’s book and just saying, I don't care how many years have changed, how many decades have gone by, we're still very much here.

Peter Hayward: It's interesting for me that you coined “shock” as an emotion and even “grief” as an emotion, but the ability to name it, to have a language for it, to have a literacy for it. I wonder whether- Riel Miller talks about us having a lack of images of futures that really stunts our ability to imagine the future. Have we also, are we also stunted by really not having a vocabulary and a richness around our emotions and things like change, and shock, and denial?

Juli Rush: Yes, 100%. I think those two things are linked, right? If we can't get in tune with what's happening in our bodies, how do we even begin to mentally process an image? How do we begin to have this sensorial experience of touch, taste, smell, to be able to imagine this future? And I think you're absolutely right. I think that type of emotional literacy is something that when we think of our younger generations, have we given that to them? Do we even have it as adults in the room?

My friend Lavonne and I are working (Lavonne Leong in Hawaii) he and I are working on a project right now that's around what are the “durable skills that future generations need”? And I'll tell you, a lot of them are emotional. And “tech is tool” -there's lots of things- but there's also this heavy sense of emotional needs and literacy, like you're saying, that I think will become paramount.

Peter Hayward: I'm older than you, and I have the privilege of living in a somewhat different world where I'm not so sure they were necessarily emotionally literate. However, it seems, if I look back that we had a culture that people were really given no choice. They were asked to confront things and if you like, build a literacy out of just having the experience of it.

And death was one of those things that death was not something that happened away from houses and away from families. Death was something that happened with, and almost willingly, it was a family social experience.

Juli Rush: Absolutely. I think in all the research and studies that I've done, this move away and not wanting to see death, it moved out of the house. It moved into expert hands, it moved into hospitals. I think it was our fear of seeing and looking. I saw a recent study a few years ago that said for the first time, at least here in the US, death has moved back home, and folks are dying at home more for the first time.

And then when you start looking at the reasons and the implications of that, a lot of the reasons are because of what's happening in the US health system. It's also a huge lack of trust that's happening between medical practitioners and so many Americans. And although I think that it will, just like anything that we look at the signals that we're looking at, if I look at this information, what are both the positive and negative implications of it?

And I think even looking at the root causes to me willas we see death coming home, how will that change us? When we're looking at something for the first time. I usually refer to it as “social rubbernecking”, that we often want to turn and look at tragic events. We want to look online when someone passes away, or I like to say, Taylor Swift and her boyfriend break up, we race to look at the internet and see what's going on.

Just like rubbernecking on a road, we turn our heads and we look at the accident to see why it's happened. And I think that really is about control and about being able to say, “don't let the bad thing happen to me”. And I'll tell the story of when my sister was dying, people would say, “but how did she get the cancer? What did she do”? And I knew what they were asking. They were asking, “how do I not get the cancer”? “How do I avoid”? So I think when we are confronted, sometimes it forces us to deal with this attraction toward despair and demise. It makes us confront ourselves in those ways.

And I think, like you were saying before, there's been a lot of talk lately about that we have “gone frictionless”. That we are building “frictionless societies” where there's no rub anymore. And how that is connected to the loneliness epidemic. That when we never have to rub up against anything hard, we find ourselves more lonely than ever.

I think all those things certainly are linked in a part of the greater system, but I think in this frictionless conversation, that folks are now going analog again, where we want to touch the world around us. I think all of that will be a part of feeling our feelings and spending time to get present to that.

Peter Hayward: So,I don't want to jump there just yet, but to some extent, you are foreshadowing that we possibly as a culture are trying to bring friction back into ourselves in order to have the experience and then build the literacy and an ability to work with the emotion and name the emotion and live with the emotion.

Juli Rush: Absolutely, and I think of Taleb’s, “Antifragile”. And I think by looking at antifragility in education, we were pushing resiliency for a really long time. We were using that term “resiliency”, and the more time that we have spent with mental health professionals when using that term, is that really the best term to be using?

So I'll often use “antifragile” or “antifragility” and use “fragility”. I think that when I am looking at younger generations-like I said, most of my time is spent with these younger generations, and it's where I get a lot of my signals from-and one thing that I have noticed with younger Gen Alpha students is they will often say to each other, “that's AI”, even if it's not in an online context, they're not online. They'll speak to each other, and it's their way of saying, “that's not real, that's fake. You're lying”. And a lot of them are saying, “I don't trust anything online anymore”. I can't trust what I'm seeing on YouTube or I'm seeing on social media. I think that creates a void, right? Like a lot of these big changes create this vacuum, and we're looking to see what is happening to Gen Alpha in this vacuum as they pull themselves away and are figuring out how to trust in the world that they're growing up in.

Peter Hayward: I wonder if there's part of it that’strust and part of it's faith. And I don't wanna put it on the tracks to saying, “because we've become a more secular society we've lost the ability to have faith in things”, but at some core level, we aren't in control. So what is it that anchors us? You talk about values, I go further and talk about a philosophy.

But are we living lives-are the younger people trying to live in a kind of frictionless, secular, faithless, beliefless operating system and just finding that it's just terrible for them?

Juli Rush: I think that what I am seeing is that a lot of them are trying to figure this way out without some sort of elder mentor guidance. And so they're trying to do it the hard way. They're trying to do it the hard way, and not that it can't be done, and not that it can't be really successful and generate a ton of self confidence to do a lot of these questions and trying to navigate all of this alone. But I'll often tell people, find yourself a good mentor, a good therapist, and a good community. You need, I think, you need those three things. And so when I work with this group of young people, I often say to them “Who are you talking to? Who's helping you”? And for some people that's apastor or a church community. For me, I think as long as they are doing that kind of work with an elder society and with folks who can guide them, they feel so much more secure.

I think for a lot of that-Gen Z, not really Gen Alpha, but Gen Z-a lot of them just don't have that around them. And part of it has been rebellion. Part of it has been doing it their own way, and also part of it is because they've been left alone. And there's not a lot of people gathering around them. So it's a little both/and.

Peter Hayward: A question that's coming up for me, Juli, is I'm wondering if this is not an area of conversation that is taught or if it's hard for people to have these types of conversations. I wonder, weirdly, and I'll say weirdly, whether this is a conversation that futures and the community, the futures community could in fact auspice those kind of conversations.

Juli Rush: I do think so. And I think there are some folks that, especially non-Americans, I think the further east we go, the more folks are willing to have these conversations. I think, I look at Sohail and Ivana's work, of even talking through the futures triangle and saying, “What is the weight of the past, what are the values and things we want to hang on to, and what are the things that we need to grieve and let go of”? And working through CLA- I’mworking with a group right now of some folks that wherean industry is dying. And they're trying to figure out how to move forward, and they're angry, and they're resentful, and their livelihoods are being taken. And so taking them through CLA and saying, “let's get down to what's actually happening”. When we talk to our students who want to be facilitators or work in client-based futures, I'll say “follow the emotion”. If someone's exhibiting some kind of emotional reaction, you want them to be emotionally reactive. You want them to get in action, right? And so follow the emotion. If they're upset or angry or all of those things, you prefer that over resignation or you prefer that over a lack of response at all. Then we're not doing our jobs right.

And so I think that those types of tools really speak to this. They may just not use the language as strongly as I do. But yeah, there are lots of futurists in the East, APFN and groups like that I think are doing some really beautiful work. Those of us over here in the States, we're really struggling.

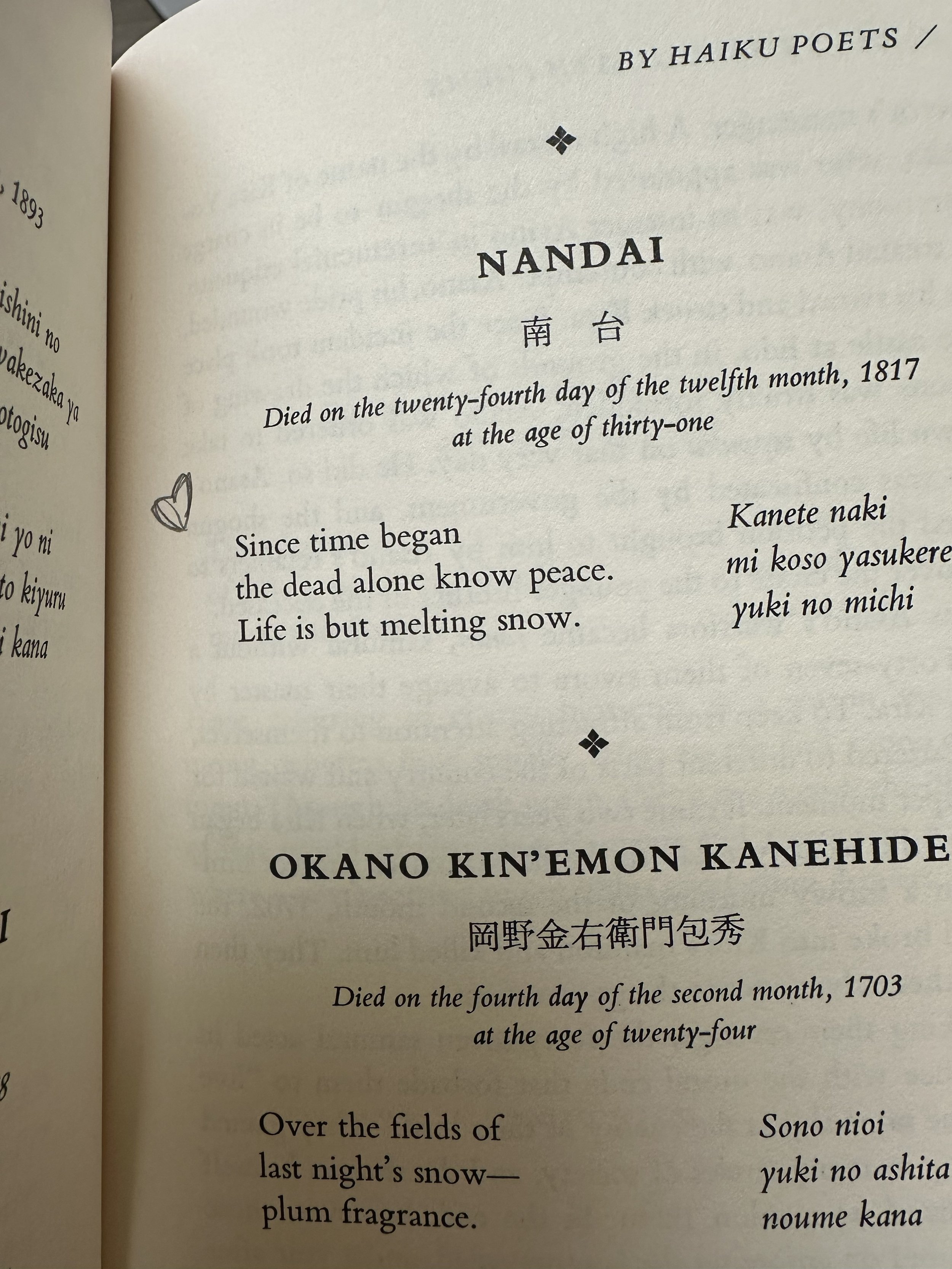

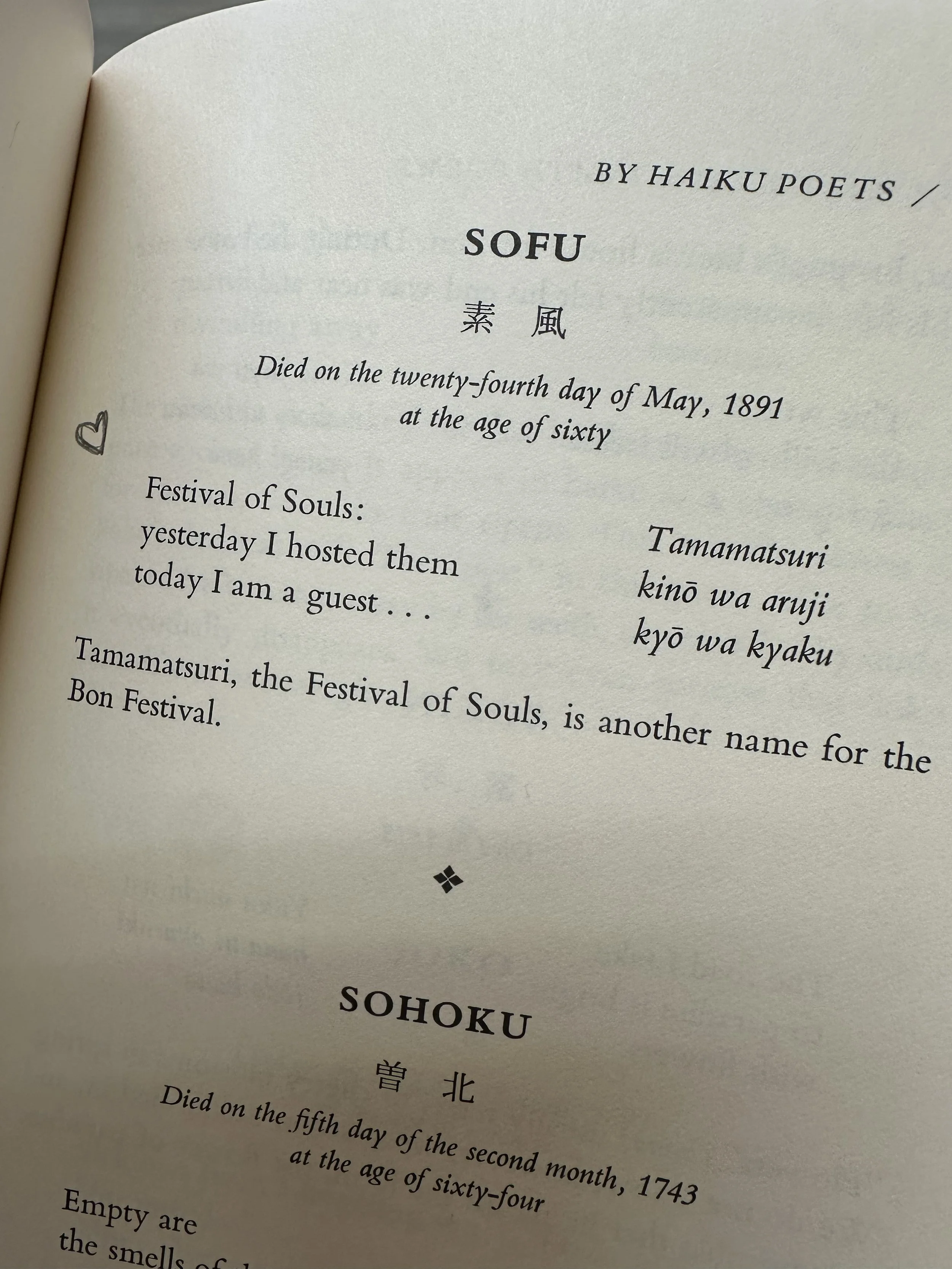

Peter Hayward: Yeah. I stumbled onto a thing called Japanese Death Poems, and I'd never read anything like it. It was just to tell the story of people- you might know what they are-that you've got Haiku, the style of poetry. You're from Japan, and if you were a Haiku poet and you were dying (because they all died), then you were not expected, but you were, if possible, you would make your last writing a poem based on your death.

And these are amazing things to read as poetry, but also the situation of the poetry. This is almost the last thing the person did, almost the last thing the person thought, and it was the emotions of when you read them, it felt so intimate, it felt so powerful and purposeful. As I said, I was absolutely- I'd never heard of these things and I just stumbled onto it.

They are just some of the most beautiful, heartfelt, philosophical things in five lines. And culturally, we have a wealth of this in the people of our planet, but how can it be that we just don't know about these things?

Juli Rush: Yeah, I actually own the Japanese Death Poems. I actually own that book. I have it right up on my bookshelf.

I think that part of it is bringing about those types of conversations. There was a kind of a trend of doing death cafes that happened, especially across like the UK. It happened really strongly. I think they, that there are groups that try to have these movements. Something that I've been researching over the past year is just around the idea of ritual.

And I think that, like you're saying, the Japanese poems is this moment in time where culturally they decided that this was something they were going to do. And whether it be like the Irish wakes and doing the Irish wakes, culturally we, we can recognize that so quickly. I think that, for us, n the States, for sure, we don't have that. You go to a church and you show up and usually you put the body in the ground, and there may be a little bit of food afterwards, and that's the extent. And you get, oh, you get like a few days of bereavement from work. And that's the extent of our ritual here.

And so looking at other cultures and customs and saying: “Where does this fit in for them”? And then, and not in an appropriation kind of a way, but saying how might we learn from these different groups so that we can bring conversation and ritual? Arnold Van Gennep was a Frenchman that was a sociologist that was going around and researching different societies and cultures. And what he noticed was that there were these three different steps regardless of where they were in the world, where it was separation, transition, incorporation, and that each one moved through this ritual and it, and sometimes it looked like the young man going horseback away from the tribe and coming back a man.

We look at it as like the the husband carrying the bride over the threshold of the home. And there's always this idea of this threshold that you must move from one space to another, and it's often physical. I think books, like what you're describing with the Japanese Death Poems, is this acknowledgement of transition and it's moving someone from one plane to the next plane.

I think if we can begin to build those rituals more and more into society, it gives us, like you're saying, this firm foundation of we know what to do. We're not as scattered. We have a pattern. I get to do a talk at a conference in Austin called South by Southwest this year, and the talk is about ritualizing grief and joy.

How are we building ritual? How are we learning? How are we embedding this? And it's taking futures frameworks and things like that nd then embedding it with this rich culture of rich experiences from around the globe.

Peter Hayward: Great. And I don't-I just wanna make this point. You've made it, but I just wanna make it again and let you remake it-we're not just talking about physical death here. We're actually taking it to a cultural meaning to the idea of the end of ideas, the end of organizations, the end of groups that this-that the same things about the emotion and the rituals or lack thereof, that we have to appropriately let things end so the next things can start.

Juli Rush: Absolutely. Yes. I'll double down on that with you. I think that sometimes when I tell people that I'm a death doula, they'll say, “can you be a work doula? Can you be a, can you be all different types of grief”? And I think that's why futures work so well with it, and linking these two things just explicitly is to be able to say that any transition-and it can be your children growing up, it can be a really beautiful transition,it can be a moment in time that is natural and is appropriate, and also has so much weight and grief to it. And that grief can be complicated. I think that when we start compounding those like in, in thanatology we talk about complicated, complex, compounded grief, lots of kind of technical terms.

And for folks who are going through so many transitions-kids are growing up, marriage may be ending, job transition, being relocated, your parents are aging. All those things just start layering and layering. And if we're not careful, it turns into this greater grief than you can manage.

I think also when we look at what's happening globally and when we look at complexity and things like that, we have this macro grief that's like the human experience of grief. Even if I am not actively in a war zone, or even if I am not actively participating in something that's happening, I still experience the human condition, the collective experience of macro grief.

And so how do we combat that level of grief? And so we talk about micro joys combats macro grief, but also micro grief allows you the ability to experience macro joy hat if I am not careful to grieve along the way, if I'm avoiding that, then how might I be able to participate in a greater human experience?

And I think that's where we lose that friction. Like we become frictionless, we become lonely, we become detached, we lose foundation and grounding-the things you were mentioning earlier-I think those two things are cyclical, dialetic. They reverse back on one another. Yeah, I think those are linked and I think when we can begin to have conversations about, “yeah, this is hard and there's probably some grief here”, it makes it so much easier to move through that than to resist it.

Peter Hayward: Yeah. One of my favorite sociologists was Zygmunt Bauman, who wrote the wonderful book, “Liquid Modernity”, which is the first book that I read that said: you are now fully responsible for what happens to your life because you can't plug into any society, any sort of historical culture to say that I'm born to a person who's a baker, tTherefore maybe I should be a baker. But you are, you are free to be anything, and you have the responsibility if it goes wrong. And it was a terrifying idea when he wrote it quite a long time ago.

Juli Rush: Absolutely. And I think teaching young people or even adults, how to be atrue Self and to identify values, that's a lot of what I do with young people is saying: let's look at values. Let's look at Self-the community, the therapist, the mentor, whatever those things are-to build who, what is the Self? And I think once people get really clear, very clear on who they are as a Self, that's when Self dissolves and Self is allowed to be part of collective and community. And you are no longer fighting the boundaries of what's yours and what someone else's, or we lose such a sense of fear and are able to show up with a lack of fear of being part of something big.

So that's a lot of we start our very first Intro class at UH with Self. We move from Self into Other and System, and carry on because it's just the conversation about systems. There are parts to systems, and if the parts are not healthy, how does that impact the systems? And then, we move into Donella Meadows and we start talking about the levers of the systems, and being able to say, “where do I fit into this? I'm not lost, I'm not alone. I'm not incapable. And so where are the levers I can begin to push”? And, the systems sometimes are meant to overwhelm us. We're meant to be confused and kept stuck. And so giving people these types of tools, I think, builds capacity to move past overwhelm.

Peter Hayward: Yeah, I think one of the things, one of the joys, is finding awe. And so actually find a system that makes you feel tiny, and you just stand in awe of 'cause it's one of the, again, another one of those joyful emotions-that smallness and being relatively powerless in the face of something more powerful is also joyous. And but again, as you said, finding these micro moments of micro joy.

.

Peter Hayward: That's a great grounding. I think we've wandered around your frameworks and philosophies and kicked a few rocks over. What's happening around you that you are paying particular attention to and why?

Juli Rush: Yeah, I think, like most of us, we have these like fun little side projects and niche projects that we're paying attention to, and certainly the death space-the actual physical death space. How are we doing body disposal? What are the new ways of doing this? What are the implications of that, for sure.

So being a death doula and sitting bedside and vigiling with someone, or helping someone with legacy, or helping write paperwork, I'm constantly paying attention in those spaces, like the idea of death coming home for the first time. Certainly paying attention there. I also, because I pay attention to my Gen Alpha and Gen Zs and their language, and the other day my daughter, she's 11, and we were talking in the car and she said my friend asked me what my “bias” is on that album. And I said, “what did you just say”? And she said, “my bias”. And I said, “tell, what did, what was the answer”? And she told me, and what she was saying was, “what is your favorite”? They're using that word as “favorite” now, right? What do you lean towards? And so it's these changes in language that I'm constantly trying to track down with these Gen Alphas, but also how they're responding to things that are happening in the world, or adult concepts, something like social media. Their move away from the digital space and how much of that is driven by parents wanting to remove their kids, and how much of it is being driven by them with this lack of trust and things. So certainly paying attention there. With my Gen Zers, they were all, they were high school students during COVID, and a lot of them are trying to navigate this massive educational debt conversation. The work -the changing workforce, they are struggling with changing sexuality, gender conversations. These types of like norm conversations, like you were mentioning, where, because those lines are so less clear, their confusion is leaving them with this sense of apathy, this sense of despondency. I think I've never seen such a sad group of people as that particular age group right now. And so being able to step into a space with them to see what might be coming for them and changing for them, and I think I listen for those kind of signals from those just being embedded with them and doing life with them every day.

But I also, I love going to conferences. I love just sitting in, going to the back rooms. I always encourage people, when you go to big conferences, don't go look to the main stage, go to the back rooms, what are people saying at the end of the day in the very last room nd be able to pick up some things there.

But certainly around the death and grief space, for sure, but more so around the upcoming generations and what they're talking about and interested in I think is really gonna shape-it informs a lot of the signaling that I include in looking at trends and things.

Peter Hayward: What's your view on people having conversations with their favorite large language model, because increasingly people are getting everything from life advice, relationship advice. You talked about having a good therapist and a good community. The language models have stepped in and are filling a need, but whether they're designed to fill it, I'm not so sure.

Juli Rush: That is a wonderful question. I think the LLM conversation to me is, I'm curious if it's our way of asking the collective. It's our way of saying, “what does the universe that I am a part of, what do most of the humans that are contributing to it think”? Because it gives us this kind of generic answer of “here's what people are thinking and saying, and here's my general response”. And so in some ways I think it's just people asking, “what would people say? What do people think about this”? I also think it's similar to, when I was at least coming upon the internet, wandering into a chat room and asking random strangers, “what do you think about this? What do you think about these situations that are happening in my life”? I think that just like any sort of cycle, we will see the other side of it. And I think there are some major negative implications that I'm watching for on the other side of this LLM AI as we move down the hype cycle on the other side of looking and seeing what is in that vacuum on the other side of it, I'm worried. I think that this push to go analog or to remove ourselves from social media and online life can be dangerous because so many people use that as a safe place, and we should be, I think, embedding ourselves in the communities that we're a part of, where we can touch another human being. We can see another human being's face. We can be hugged, and felt, and touched in a part of something together. And I worry that when we spend so much time in that space, whether we are hallucinating or the AI is hallucinating, that we lose touch with reality. My daughter is currently watching a show online. It's based on the short story: I have a mouth, “I have no mouth, and I must scream”, nd it's about some people who get trapped in a VR reality. And I'm talking to my daughter about how, even though this story was written a long time ago, that getting trapped in this alternate reality is part of the reason why I want her to be out experiencing the world and not get lost in this psychosis of online life.

Peter Hayward: Yeah.

Juli Rush: And I think she's understanding. She will tell me she needs to go “touch grass” is how the kids say it. “I've gotta go touch grass”, and I think we're on the right track, but as a parent, it's quite intimidating.

Peter Hayward: I'm sure. The other one that you mentioned, elders and having elders in your life and, one of the things that I've felt most grief in is the lack of public eldership. That we now appear to have a combination of a media environment and a set of leader behaviors that kind of came together to create a perfect storm. The people that are picked up in the media and amplified through the media are often the least, you would say, practicing social eldership. The least likely to be acting the way that people would say, “act like them”. Those people are still there-those people are still there in their millions, but we don't feature them. And I wonder where people find their elders.

Juli Rush: Yeah, I think is it Longpath? This the book that's written about like the seven generations-trying to remember the name of the book. Yeah. And speaking of being able to guide generations and being a good elder. My friend JT Mudge, who's also a faculty or adjunct faculty over at UH, we will often talk about how younger generations will look back on us and our lack of care for the environment the same as we looked back on our grandparents around slavery. And that the amount of shame, and embarrassment, and frustration, and anger at our lack of care for the environment is one point. But I think that there are several other places: the social architecture that we're not taking care of, like you're describing, what does it look like for them to look back at us and say, “you didn't save us. You didn't help us. You didn't guide us”. I think that is a huge sense of grief right now for younger generations. I think this is a place where I'm paying attention. I think that we have to decide, I think for my generation of raising young kids, connecting them to grandparents, and I think there was this move towards Selfness. I just talked a little bit about Selfness, but self-regulation, self-care. Self, lots of so many Selves that we pulled awaythe pendulum swung away from the community. And I think in our independence and in our Selfhood we pulled ourselves too far and are moving back towards the community conversation and saying intergenerational community, allowing elders to participate, eing able to connect young people with elder generations, I think, will become really important, especially as some of the older generations are dying out. My my parents' generation, for sure. I think that they're trying to build legacy and we talk about digital twinning and, there's all these new technologies we've been talking about how to retain and connect with people who have moved on and maintain some of that.

I think that when I look, especially in the States right now, of what's happening politically when we see who's being accused of what, and when folks wanna be able to look online and be able to point to someone that they trust, it's not gonna be in the media, it's not gonna be online. It's gonna be the people living in your community that you're a part of.

And so how do we push back towards that-to living more local, to doing community more local, that a person that you can trust that's embedded in the life that you're living. I think that's a choice for all of us who are on the older side. And I'll include myself in that. How do we take that seriously?

Peter Hayward: And I would imagine that absolutely transfers over into the workplace where we've got the younger generations coming into the workplace and the older generations may be stepping out of the workplace. And what needs to happen in those organizations is that same thing that what can be passed on, is passed on. Respect is shown, rituals are established, but at the same time, people leave and get out of the way. It's a very complicated process, eldership, isn't it?

Juli Rush: It is. And I think young people have to be given the permission to risk, and to reach out to elders too, and say, this isn't, it isn't just on the elder to seek out young people for mentorship and connection, but I also think it's true for us to do the asking. I tell the University of Houston students often, if you read an article that you like, email that futurist, email that foresight strategist and say, “can I chat with you? Can we have a conversation”? They, I think, undoubtedly, would be happy to chat with you often.

I've done that myself, just shot an email. There's a woman who was a futurist and I don't know that she would call herself that now, but reached out to her and just said, “could I chat with you”? And she said, “I wrote those articles 40 years ago”, and I said, “I wanna meet the person that wrote that, and I wanna hear who she is now after 40 years of living this life, would you be willing to be connected”?

And she put in the mail her dissertation, she sent me articles. She, we became pen pals, and she's no longer a practicing foresight or futurist, but just hearing the life that she led after writing those articles became really important to me. And so I tell the students all the time, whether you hear them on FuturePod, or you read an article, or you hear them speak, get connected to them because they, I think, want to be leaving legacy as well and be connected to younger generations just as much.

Peter Hayward: Very true, Juli. Very true. Communication. This is probably a touchy one for students and foresight: what do you call yourself or how do you describe yourself? To the, when you come back to work after or the family or whatever. I've had some lovely Futureods where the person's said the hardest person I had to explain to was my mother, but what are some of your communication challenges and some of your communication strategies?

Juli Rush: Absolutely. Teaching Foresight Framework or Future Thinking and Systems Thinking is the only classes that I teach at this school that I'm at, and so often the parents will say, “what are you teaching? What are you doing? Explain to me”. And those are always fun conversations when the middle schoolers go home and tell Mom and Dad, what Ms. Rush was trying to teach them in class and how they're a part of the systems and how they're going to break the systems intentionally. So those are great.

I think I will usually tell folks, you don't lead in that. I think it was Mina McBride taught me this: She said, “you never want to lead with, Hi, I'm Juli, I'm a doctor”. You don't usually lead with that, right? You lead with the other parts of you, of here's what I'm up to, right? Just like that values conversation.

And so I'll usually tell folks you can, if you call yourself a futurist or a foresight strategist, I don't know that those two things dramatically matter. I think perhaps Andy Hines and I would disagree. I don't know. But I think different people choose different terms for themselves.

I will usually just say that I try to help people anticipate the future. I try to help them build a resiliency and an emotional capacity for the future. That's the broad term that I use. But I think you're right. My daughter will often say, “Mom just talks about robots. Mom just talks about robots”. And I'm like, actually that's the one thing I'm trying to avoid is the technology part. That will see itself through. It's all the, as we said, social architecture and everything else. But yeah, I think, less about the title, more about what you're valuing, what you're attempting to do with the work.

Peter Hayward: So Juli, we're we're almost at the end of what's been a wonderful conversation. I'll pass it over to you to just bring this ship home.

Juli Rush: Yeah, thanks. I think, if folks were to leave with anything or how to think about this differently, I think there are some folks doing some beautiful work and I'll share any of that with you, Peter, of where to send them, because I am certainly not the only one in this space doing this, and I wanna acknowledge some really beautiful folks up to this.

But I think especially in the death space, like you said: reading Japanese Death Poetry. When folks ask me, “how do I even start on this journey”? I'll tell them “poetry”. I think it speaks the best to death. Just like poetry speaks the best to love. We look for song lyrics, we look for poetry. We find ways of saying what can't be said.

I think those are some beautiful ways to do it. I try to post book reviews and try to post and share about things that I'm reading that I think are beautiful in that space, but but also just love being connected to folks. If you need a death doula, if you need to talk to somebody about grief space, for sure.

I think at U of H where we're doing a lot of this work too, as practitioners if folks are ever curious about what we're up to, we'd love to chat with them. And also just for folks to keep having these conversations. If I could leave listeners with anything, it's just to, to be the person that says, “do you think this could be grief? Do you think some of what you're experiencing could be grief”?

Peter Hayward: Awesome. Juli, it's been a wonderful conversation. I'm so grateful to Lavonne for introducing us. So thank you for spending some time with myself and the Futurepod community.

Juli Rush: Thank you for having me, Peter.

Peter Hayward: Thanks for a stimulating and wise conversation. Just so much in it for us to reflect on. And bring some friction into your life. Your future self will thank you. Future Pod is a not-for-profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support the pod, then please check out the Patreon link on our website. I'm Peter Hayward. Thanks for joining me today. Till next time.