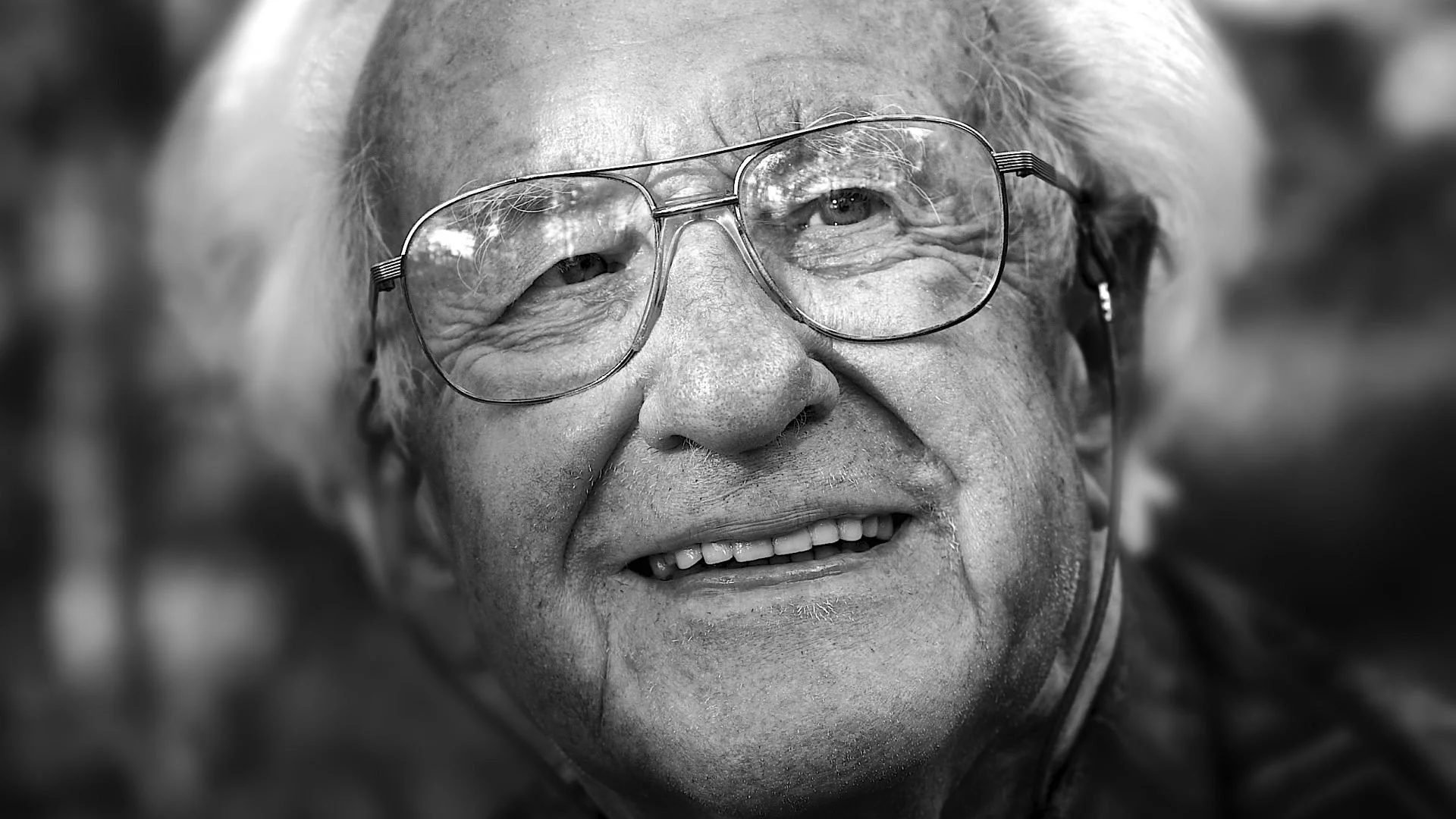

A conversation with Sohail Inayatullah and Otto Scharmer remembering Johan Galtung, a Norwegian sociologist and the principal founder of the discipline of peace and conflict studies exploring who he was and what he meant to them on their work.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

References

Audio Transcript

Peter Hayward: Standing on the shoulders of giants is a metaphor meaning that current knowledge is built upon the knowledge and achievements of those who came before. Today we remember a giant with the help of a couple more. So who was Johan Galtung?

Sohail Inayatullah: I still remember his 1981 lecture at the East West Center. And he stood up and he talked about his new theory of politics in the future. But the striking part was as he analyzed world systems, world civilizations. He said, by 1990, I forecast the Soviet Union will collapse. In 1981 it was a big call. And the entire audience erupted into cynical laughter.

And then someone asked, why are you so confident? He said systems that are structured in authoritarian ways don't have room to maneuver. When external forces hit them they're not adaptable. They can collapse.

Otto Scharmer: There was one person who completely used science in a different way. And that was Johan Galtung. He did a lecture series and I attended that and I was just transfixed because his methodological approach. Science not cementing the inequalities that we already know and explain why that is, but science as a process to seek and break the in variances. He was always interested in human awareness, human consciousness and that's what I picked up. That's what I'm still doing.

Peter Hayward: Those are my guests today on FuturePod. Sohail Inayatullah and Otto Scharmer who are here to help us remember Johan Galtung

Welcome back to Future Pod Sohail Inayatullah

Sohail Inayatullah: Great to be here, Peter.

Peter Hayward: Now Sohail, you know that I was trying to get Johan onto Future Pod with your help. We sent some messages to him, but it didn't happen. Circumstances as such. And so you have done one of these remembering podcasts where we just give the listeners a chance to hear a bit more about who the person was and you were keen to, to come on and.

Participate in the remembering Johan Galtung. And you've brought a friend with you. Do you wanna introduce the friend that you've bought?

Sohail Inayatullah: Yeah, this is Otto Sharmer. We were strangely enough in a gradual class with Johan in the 1980s, and that led to a book, macro History, macro Historians, Otto since gone on to develop Theory U.

And is foundational in ways to approach social change, being in and outer perspectives. So I think to reconnect with Otto here is just fantastic. So thanks for creating the space. Peter,

Peter Hayward: welcome to Future Pod Otto Scharmer.

Otto Scharmer: Thank you Peter. And bringing me into this conversation. It's it's we are privileged to be part of that.

Peter Hayward: Thanks mate. So I'll ask the first question again. The question rests with both of you but I'll ask it once. Who was Johan Galtung and how did you meet him?

Sohail Inayatullah: So for me I would've read his works first before we met in the late 1970s.

His empirical. It was a structural theory of imperialism, but it was based on it's a, it was an empirical data led, so we read that in our normal political science classes on comparative comparative economic political development. And then we were fortunate he came to Hawaii, I think 1982 or three and gave a series of lectures.

And I still remember his 1981 lecture at the East West Center. And he stood up and he talked about his new theory of politics in the future. But the striking part was as he analyzed world systems, world civilizations, he said, by 1990 I forecast the Soviet Union will collapse. Wow. And it by nine, in 1981, it was a big call, and the entire audience erupted into cynical laughter.

And then someone asked, why are you so confident? And Johann was always confident, but this wasn't about that. This was about, and he said, systems that are structured in authoritarian ways don't have room to maneuver. They're tight. When external forces hit them, they can't, they're not adaptable, they're not agile.

They can collapse. And so he was very clear the Soviet Union is going in that direction and he was already on some list. And so that would've been. That's when we first read his work. Then went to that lecture and then I was already writing around Sarkar social cycle, so I sent him some of my essays and then he invited me to, he got a visiting professor, visiting University of Hawaii.

So I went over to meet him. I had three essays. This is the late eighties, and he said, this is great. And now what? And then the now what became a, why don't I start my PhD? So Galtung agreed to be the main supervisor with Jim Dader as the facilitator, the one who handled, the emotional, the the connecting parts.

So for me it was just brilliant to have, Galtung as my supervisor and he was. Fantastic to work with, but not for everyone. So in terms of who is Galtung, so I prepared, in the US there's proposal defense, and that's a 35 page document to your five members of the committee. I had Datar, Galtung, Michael Shapiro, the gold theorist, Bob Bobin, the religion professor, and Bob Stafford, the comparative politics.

And Johann looked at my proposal and just threw it in the garbage. He said, here's what I think of your PhD proposal. And then I, I looked at him slightly, crest ball, 'cause it took me, about a year to write those 30 pages. He said, this is just junk. And I said to explain why. He said you need to take Sarkar far more seriously as one of the greatest thinkers to ever live.

Don't gimme a normal political science PhD. This has to be sarkar with marks, with gramsci, with Vico, with chardon, with the big picture thinkers with Ha K and Sumia Chen. And so the way you've done it is just junk. I said, Johann, okay, I'll change it. My proposal defenses tomorrow at noon, he goes, looks at me.

He says, if you can't write 35 pages in 24 hours, don't wish her time with me.

So I'll talk more later, but I think let Otto come in here. And so this was both, very confident person, of course, amazingly brilliant genius in terms of. Explaining big picture stuff and very direct. So in today's language, he didn't suffer fools gladly. I think that was the term people made and some people really, yeah.

Didn't like that. But I found, in terms of me working, he understood I needed a challenge and I would rise to the challenge. He wasn't about to treat me with kid gloves. He was like, no, you want to do this. Let's do this.

Otto Scharmer: I love that so much. This story Sohail, and it brings just memories up on my own. To your last point,

it's a small remark Johan did in passing because he dealt with very serious issues as we know,

but,

He was very funny, right? Personally, he was very funny.

Without humor you can't do any of this, right? Kinda, yeah. Without getting sour and so on. So he I remember, I think we was driving in a car or so and he said in passing. Yeah I don't have false Modesty, right? Pause. And also not true one.

That was just a little footnote to the story you shared earlier. But next how you met him first in 1982? 1983, which was exactly when I met him too. And on the other side of the world in Berlin I just finished my back. Then we had arm Army service in Germany, so I refused to go to Army.

You would go to a trial and when you succeed in that trial, you could do a social service, which I did. And then once I completed that. I started my studies. I went to Berlin, the free University of Berlin. As a freshman and I was pretty, that was probably one of the biggest disappointments of my life because I had been looking forward to entering a university for many years.

And now I saw the medioc of that institution. That was pretty disheartening. But there was one person. Who, completely used science in a different way. Who stood out really in that way, and that was Johan Galtung, who was a visiting professor at the free university for of Berlin. The, I think the Bergman Institute or something.

And he did a lecture series about his stuff and I attended that and I was just transfixed because essentially about his methodological approach because of using science. To seek and break in variances, that was essentially his methodological base. Science, not cement kind of all the inequalities that we already know and explain why that is.

But science as a process to. Seek and break the in variances. And in terms of breaking, of course, the main third variable he was always interested in is human awareness, human consciousness. And that's essentially what I, in hindsight, what I picked up. That's what I'm still doing.

But I got that you could science. That you could use science in this way and engage directly with practice, with the real issues in the world and real players in all these areas of conflict and change. That was a profound inspiration for me. And it's interesting. I was a pretty depressed freshman there, by what I saw otherwise.

It only takes by the institution that was surrounding me, but it only takes a single person who is operating from a very different place to ignite a flame that has since never passed.

Sohail you probably remember, I think there was this triangle, right? Of data value and theory, I think it was. And so basically he was advocating and he was then situating. And identifying three different bilateral ways of science.

Empiricism one, and then, constructivism another one, and then critical theory, a third one. But what he was advocating for is integrating all three. And so that, that was really the inspiration for me. Now, I then took all my courage together and approached them. After, because I was also active.

I was active in the East German Green and Peace movement at the West German, but also in East Germany because I was running into all the dissidents in West Berlin. So I was the guy I could go to East Berlin. I was connecting things. And then I organized for Gaton a seminar in an apartment in East Germany, an illegal event for the East German Peace movement in East Berlin.

That's how I got to know him personally. And then I left free that university after a year and went to, small university in western Germany, that was just launched back then. Wit had university, so it's a private university. Then as a student. So it was basically a university based on, engaging more with practice, bringing in a deep reflection into the various disciplines.

And also. Based on student activism, right? Student agency. So part of that was we as students were able to organize a conference there. So I invited Galtung into that university and he so that was, it's, it was a very small place. There were only like 50 or 60 students at that university, or maybe a hundred back then, but 60 or 70 were in the room, right?

It was the room was completely filled. There was an awesome expectation anticipation. And I was, it was a conference around the dawning of the Pacific Age. So that was the title I was giving the framing. And like you sohail right? A year or so, right?

I put it to the preparation and all the people there. I framed what our question was and invited then Johan to launch into his seminar, to give his keynote and his workshop. And I remember and I was nervous, but I was happy when it was over.

I thought that went okay. It went pretty well. And then as I was sitting down, Johan took the the microphone and said, thank you so much Otto, for what you said, pretty much everything you just said is wrong.

So that was the opening line, right? Pretty much everything said that was wrong. It's, it's kind of completely wrong or was wrong. I think he said, and then he en large enter to explaining why that is right and why he saw it in a completely different way. But it was pretty much so when you Sohail shared your story, that was my experience.

And until this day, I think that was probably. The intellectually most exciting workshop I ever attended, right? Because he gave it his all right. Everything that he all the frameworks, all his work, it all went into this. He stayed for a week. We had a living community back then, like a student community.

So we rented an old house. We are living all together there. One room was for him, so we had a room for lecturer there, so he was staying in that house. And as a result of that seminar he got a visiting professorship at that university and he came for, must have been a decade or two to that university every year for a week or two and would stay in that house.

And so when I was there, for those years, we would then have these seminars and he would be also part of the living community. Then maybe the last point, kind of this early years I remember one morning, so we had a breakfast with him. The dean of our department was there.

And one of the students asked him, so Johan having accomplished, he had this CV, right? At 50 universities, and I dunno how many papers, whatever. Having accomplished everything you have accomplished, Johan, that student asked,

what is it

that's left for you? So what is a big idea you have never realized?

And he puts down his coffee and he says, you know what there is an idea. And then he described how he would bring together an international student group

and

travel with them in our peace studies around the world, right? From all corners of the world. You would start in Washington and then go east and each major culture you would study while politics of peace and conflict.

Use culture to understand conflict and religion as a key to study culture and go in each of these major world cultures to the center like Moscow and to the periphery like Estonia. That was before the collapse of Soviet Union and then he described the entire itinerary for eight months or something like, and at the end of that description, I knew we were going to organize that.

And it turned out he tried that idea with Bard College, where he was also a visiting professor, but they couldn't put it together. But then we formed the five person student team and we put that program together within, a year and a half. And it took a year and we traveled then with them in the years.

88 and 89. So before and after the collapse of the Berlin War and when we met in Hawaii, Sohail, it was right before the launch of that trip, and I was then a student assistant of Johan's. I was the kind of student executive director of that program, and he was the academic director and part of my work.

Then in Hawaii, where we met for that macro history seminar was the preparation of that trip. But then when we took that trip. We went to East Berlin and Eastern Europe. Shortly before the wall came down, we talked to the dissidents, right? And to the leaders. And what was so fascinating is to see. How no, one of the very people who were at the front line of bringing down the wall were aware of the impact, right?

Their work was about to have, and it was only Johann who predicted already years before, but also then throughout the entire trip that by the end of that year, 89, the Berlin Wall would come down, right? So it it came a little bit a month ahead of schedule. But so it is it taught me,

even

though I had seen in Eastern Europe and East Berlin and Western Europe, the same data Johann saw.

That he was the one who could predict the collapse of the Berlin Wall. I, being an activist and East and West, was unable to see that because I was too much part of the collective thinking process. And the experiences that we thought, and I wasn't really taking seriously. The cracks in the old system that were, are quite visible in hindsight.

So that's a little bit my way in to that story that covers the beginning of the eighties, but also with the peace studies around the wall trip the late eighties.

Sohail Inayatullah: Let me jump in and Peter, if it's okay. So those are the stories. If you look at Galtung's work, I think the first phase is a structural theory of imperialism.

Essentially that there's cores or centers in the world where power knowledge accumulates, and they tend not to use it for innovation, but they use it for violence towards the periphery. So you have London, Paris, New York, where the center is, or Washington. Then you go periphery in the south. So that's the center periphery.

But I think where Johann added was within the center, there's a center. So there's a core elite, and then with the periphery there's also an elite. So the elite in the west, the center of the center and the center of the periphery, they can have a conversation. 'cause they both want power and elitism. The way the system works is the periphery in the center, the poor in the US and the poor.

In India, for example, they should be aligned, but the structure of Imperialism ensures they're not aligned. So that was insight one, and he developed empirical evidence to actually support that. Insight two for me is when people look at future of religions, we were together at the Barcelona UNESCO meeting, Dalai Lama showed up there as well to talk on the future of religion and Johann's Point is the heart and every religion cannot have a conversation.

There's a central elite, but the soft in every religion can have a conversation. The soft is a spiritual goal. The mystical. The connective, so it's never Christianity versus Judaism versus Islam versus Buddhism versus Hinduism. It's the hard in each group creates institutional power and then pushes away the soft.

So that was the second big insight. The third one was, if you want to look at the future of the West, stop talking about crisis. 'cause the definition of the West in itself is crisis. There's no poly crisis, there's no meta crisis. There's no big crisis that many futures keep on climbing. He said, that's nonsense.

The definition of Western civilization is there's always gonna be crisis. The crisis creates both the innovation, but also since it's exports, the crisis to nature, to females to periphery, it means everyone suffers. So I think Galtung's structural view is you cannot see these things outside. Its deep structure.

So that was the third huge insight. And so if we look at the future of the West, you have to think why will it survive? And he said, because it's structured not just as crisis, but it has its opposite in it. So there he was using Freud. So the West is both aggressive, future oriented, progressive, but also has this gentle part, the hippies, the feminist, the spiritual, the mystical.

It's success in survival. 'cause it includes both.

Peter Hayward: And Sohail does that mean what you said? That in authoritarian societies, they don't have the relationship with the, soft?

Sohail Inayatullah: Yes, they push that away. That becomes witches to burn as opposed to over time, this is actually keeping our civilization moving forward.

We can use that as knowledge, use that as inspiration, use that as fodder for the next phase. So I think for futurists, the point, I use Galtung's way to do scenarios far more than, as my view towards the shell stuff, trends, uncertainties, that's to the height of bad foresight. Galtung says no, use contradictions.

So he was Hegelian in that way. So everything has a contradiction, a yin yang, a vja. If I understand the contradictions, then I can develop my scenarios. If I don't know the contradictions, then I'm just looking for uncertainties, which are a litany, superficial approach to foresight. So that was would've been phase one of Galtung is the structural part.

Phase two was I think when Otto met him, which is why, wait a second. We are here to do agency to change the world. And so then it was doing peace conflict studies and always trying to move people from A one wins, he loses, B wins, a loses some compromise, but essentially can we come to the transcend moment?

He said, so he said his phase one in his career was giving him legitimacy as a global professor to actually do what really mattered was creating in or outer peace. Then it was this whole experiment in Buddhism and meditation and vegetarianism and also in every situation, finding ways to find peace. And then of course you really have to bring in his partner Fumiko which for him represented I think his in East Asia, yin yang, dowist approach to reality. So he saw the world in structure. When I met my partner, Ivana Milasovic I was coming from Hawaii, Pakistan. Ivana was Yugoslavia. He goes, of course, perfect match. I said, why Johan? He said soft Islam soft communism, Yugoslavia.

Perfect match. So who does that? He did explain it in terms of most people when they think about matching, he went to deep structure of the civilizations. They were both inhabiting. So for structural politics, huge insights for people with future religions, huge insights for futurists scenarios developed through contradictions, and I think one of his best papers in future studies, there's quite a few, but the Kyoto Forum where he and Dator and others form for World Future studies Federation.

But the one I remember the most was about the year 2000, and he interviewed thousands and thousands of people, and his conclusion was he did into the year 2000, a reflection of his piece on. The future from the year 1970, about the year 2000, he said everyone wanted peace, humanity. What we got was technology.

Yeah. And so that was authentic view of looking at what happened. Then his, again, commitment was how do we create futures that are peace oriented? So those are, I think if those are the four stages in terms of seeing them. And then our book with Otto and myself and Johann did together was macro history and macro historians.

So let's put the big picture people together from Hal and Zakar together and say, what do they offer the future? How can we use them? And I think why that's useful is futures overly get into trends, even emerging issues, what's new? Instead of saying, wait a second, macro history suggest. There are deep patterns to the past, and if we wanna be good futurists, we have to understand what are the deep patterns of the future.

That doesn't take away from agency, but as Otto said, we're in this dance between value theory and methods. So we're always doing structural agency, and then we bring on our values, whether there's spiritual, materialistic, we use our values to create the next wave of change. So that would be my summary of Galtung from the sixties to, to when he passed away.

Otto Scharmer: So maybe just to add a few footnotes Sohail to your great summary. From my angle. The first one when you talked about the structural a piece that inspired me very much was his cosmology work. Yeah. He was basically working on, so the cosmology is.

The worldview of a civilization and Sohail's point, the western view he shaped in terms of two different ones, the expansive one, which is everything we know about colonization and so forth. And then the expansive Contractive was the other term. And contractive is, for example, the Middle Ages.

Yeah. Yes. Non expansive and the inward growth, like inner growth, not outer expansion. So that is civilization is actually more than one thing, and which of these dispositions are we actually embodying and enacting and activating?

I think that was, that was a profound insight for me. Then of course, in as everyone knows, in peace research, he got famous for his theory of structural violence. Basically seeing that, extending the notion of direct violence, you have a victim and a perpetrator, the situations where we have lots of victims, but not individual perpetrators, but it's a structure, like an economic or other structure as as perpetrators. And that, of course, is something that. As a category of thought and analysis is even more important now than it already was before. And then the third dimension in his violence theory of violence is cultural violence.

And cultural violence is essentially all the assumptions that legitimize structural violence and other forms of violence. And to me that has been really a profound insight. Insight. I have I, I would've loved if he would be part of this conversation. Here I would ask him whether there isn't like a fourth violence, which is attentional violence, which is not seeing someone else in terms of who they really are.

And that's gonna where. For example, not seeing someone else as a legitimate other. And so he would then respond probably that he says, yeah, that's part of cultural violence, right? But, you could also, I think you could argue either way. And then of course, another core concept of his that he brought into the conversation is the whole concept around peace is more than the absence of war.

Peace is more than the absence of violence. In other words, his concept of positive peace as something that. In spite of all the, issues we had with one another in the past, one actually is the future that we want to create together and that we need each other for in order to, and that's of course has to do with, yeah. Building different futures and it brings in the economic and the political and the cultural dimension and is also very much related to the work I think that we both ended ended up doing. In different contexts, but johan's emphasis on peace being more than the absence of violence was really a big starting point for that as well.

I

Sohail Inayatullah: think, Otto, what you add, which I appreciate is so if you look at CLA, right? Direct violence, direct peace, structural violence, structural peace. Epistemological violence, peace. And then of course for me, what I bring is the unconscious level for the archetype metaphor. But I think what I appreciate about what you do in all social engagement, you bring in the presencing, the mindfulness.

So here's the structure. Who are we in that, not in terms of words, but in terms of energy, who we are. And the times when I do that in a workshop or speech, everything changes. 'cause now we're present to the situation. I think that's a huge contribution. I think Johan would be very happy about that. I know when I was nervous when I was driving, when I went to Hawaii in the eighties, we, he had a talk at the Hawaii Economic Development Authority and so he walked in and he gave a one hour talk with one little piece of paper with four notes.

And I said WTFI would've been 25, right? The first speech I gave, the CEO fell asleep. My second speech, chief Justice of Hawaii, fell asleep. So Johan's one hour, no one fell asleep. People were focused. So I said, Johan, how did you just do that? 'Cause I was looking for an image. The future, how do I become better?

And he goes, Sohail. The first thousand times I felt anxious. And that was really good. Once you know, you find your theory, you find what works and you just stay with the craft.

Otto Scharmer: Yeah.

Sohail Inayatullah: Which is I think a very East Asian way of saying it, but I think also because he would take an event and this is what a good futurist does, you bring presence or way to think about it differently.

So most of us live in just superficial reality. I remember his one talk on ways of knowing and knowledge. So you are an event and then you see different cultures and then you see them just as they are. And you had said, no, a Japanese conference will do commentary 'cause that's sutra based civilization.

The conference held in Berlin. Then in Berlin, they're on different mountains screaming at each other. So you have the Jungian gang, the Marxist gang, the Sche gang. There's no way they're gonna dialogue each other. They just scream across the mountains. You go to Paris and no one cares why anything.

But is it elegant? So for Cole, it's the language of the language. And you, and you can look at all French critical thinking. It's all about language, right? And then I said, so what about the US equals us? And Anglo culture is obvious. What's the solution? Gimme the bottom line. So it's more what appears to be, I can't understand what's going on at this meeting.

Suddenly there's a structure to understand there's a knowledge structure and there's a power structure. And that if we do that well, gives us actually liberation. We don't get frustrated 'cause we have a way forward. And I think again, what you brought is there's not the structure, but there's a presence and if you attend to that presence, there's peace, possibility.

Have I got that right?

Otto Scharmer: Absolutely. And Johan also very much deserves credit for that because I remember when we took that peace studies around the world group. Of course, we went to India, we studied at Gujarat, VDIP. And ahimsa and satyagraha as principles is exactly what you just described.

It is the the love for truth and also the embodiment of that. I think it is the kind of presence you describe is what Gandhi embodied and brought. Development and change and nonviolent conflict resolution. And he was, and remains the major source of inspiration for everything Johan did. So if you would use one, term, one line that he quite frequently used and that would summarize in a quite accessible way what he is standing for. It is peaceful. Peaceful means. That is who Johan is. That's what he's standing for. And that is his gift that he receives from Gandhi's work and that he then as the founder of Peace Research, as a science brought into our world.

Peter Hayward: If Johan was around now, the world of Trump, the world of what's going on, the continuing falling apart of institutions and culture in the west, certainly and the rise, maybe the stagnation of. East Asia as well. But if Johan was around now, what would he be saying and what would he be advising we should do?

Sohail Inayatullah: He should, if you look at his book right at the End of the American Empire. And then what? And so again, his conclusion was you can manage one or two contradictions in a nation or civilization or five, but you can't manage 18.

If you have so many, then it's easy to predict. And I think when us started the invasion of Iraq, he said, now the acceleration of the decline will hasten. So I think his conclusion was, now that US is part of genocide and Gaza, it will just keep on hastening. So that would be a conclusion. One, the tion is ending riper and riper.

Then conclusion two would be don't 'cause it's structural focused on solutions. So I remember his work on the true worlds. What will the world order model system look like? A new United Nations, a new world government global governance. Focus on creating that. And wherever you can find peaceful solutions.

'cause that mess, I would say would be a bit inevitable now. It's not something you can go in and fix it with bandaid. It's a deep structural issue and civilizational as well. So that's my take. Focus on the peace Focus on a new global governance system and keep on looking for parties and groups who can help create that.

Put your energy there. This game is done and Trump is just the last part of that final game. I know.

Otto Scharmer: Otto does that make sense? Yeah, no, absolutely. And just to compliment what you said earlier, so he predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union by 1990. He also predicted the collapse way before it's happening now, the collapse of the US Empire by

2020.

and then basically, what is Trump? Trump is, and he said that, so it's not like imagining what you would say, but he did say that he's accelerating that process. So he is not changing the trajectory is just accelerating the the timeline. And so the focus therefore is exactly what, what you said Sohail, it is creating these I think one evocative term that I'm currently using that I picked up from Ilia is islands of coherence, right? When a, the system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos. Have the capacity to uplift the system, the entire system to a higher order.

And I think it's that's really what, who was Johan Galtung, right? He was traveling around all the time. He was always attending to these little islands, and supporting them across institutions, across countries, across communities, going to. Where support was really needed and supporting kind of these places directly.

Also coming back and when I look at what you are doing, sohail from outside and also my own patterns is that's pretty much the lifestyle we adopted too, right? We are constantly, trying to be in support of creating these islands of coherence. Sometimes in the heart of the conflict, sometimes but often around the edges, right?

And often more edges of institutions or on a grassroots level, because that's where the next, I would say. When this civilization the course of that, and this kind of empire is running out its course and it's happening now as we speak and when the process of collapse is completed, actually the new needs to be.

Created, seeded and cultivated and linked up with each other through these islands before. That's how nature works, right? The new works inside, around the edges of the old. And so I think that's what a lot of change work is about, and that's why. One of the biggest challenges, perhaps he would also say is today is actually the illusion of insignificance.

That people look at this big mess and say, there's, it's that's too big, right? Whatever I do or not do is totally insignificant where we are going, and I would say. Based on what you said, Sohail. Johan would disagree with that because he said exactly. It is in these moments where these small solutions these small living examples are the most critical thing and will take us into the next wave as we move forward.

Peter Hayward: Thanks Sohail and Otto for sharing and remembering a remarkable person who's done a lot for our field and inspired you two guys to do a lot for our field as well. But thank you for doing this and spending some time

on Future Pod.

Sohail Inayatullah: Great. Hang out with you, Peter. Great seeing you Otto. See you soon.

Otto Scharmer: Thank you both. Yeah. Take care.

Peter Hayward: Thanks to Sohail and Otto for helping us remember a giant of our field. Future Pod is a not-for-profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support the pod, then please check out the Patreon link on our website. I'm Peter Hayward. Thanks for joining me today. Till next time.