A return conversation with Dr David Lindsay-Wright who is a Futurist, Educator and Filmmaker about his latest venture. A communities view of their preferred futures(s) for Brisbane, Australia and that approach to futures work as compared to expert or decision-makers driven futures work.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

Links

Transcript

Peter Hayward: It is good that organizations are taking the future seriously. There are organizations that will publicize scenarios of possible, even preferable futures on their websites. But is getting experts and decision-makers to report the futures that they're interested in the only, or the best way to do it?

David Lindsay-Wright: If you go to any city council or regional council website, you're likely to find scenarios of the future that now seems to form part of their KPIs, and that's not a bad thing, but there's a sense that they're written by people in council, for council you get a sense that nobody ever reads them, and even if they do read them, it's in one ear and out the other, or one eye and out the other. And nothing really ever happens about them.

Peter Hayward: That is my guest today on FuturePod, Dr. David Lindsay Wright, who is a futurist and filmmaker who is returning for a chat about his latest production. A community’s ideas of their preferred futures.

Welcome back to FuturePod David.

David Lindsay-Wright: Thanks Peter. Nice to be back.

Peter Hayward: You realize it's been almost three years since we spoke?

David Lindsay-Wright: Which means that the last time would have been during COVID it would have been yeah, March 2021 right in the middle. So we would have been in lockdown at that time.

Peter Hayward: I'm pretty sure we were.

David Lindsay-Wright: Things have changed. It's almost hard to remember those days now but yeah, there you go.

Peter Hayward: Now I am going to remind you something that came across in that podcast. How important The Ascent of Man documentary series was to you. And I don't think you signed off saying you wanted to do a futures version of Ascent of Man, but it was in the background and I understand since we've spoken something has emerged. It mightn't be the next Ascent of Man, but do you want to talk about what you've been doing?

David Lindsay-Wright: I can and it's good that you brought that up because actually that, that project has been in the actually not the back of my mind, but the front of my mind for the last few weeks now.

I'll tell you why, because I've, I just finished a feature film a few weeks back and I've been looking through all my various project ideas and I have a few and the one that keeps popping up is Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man. Yeah, and I have a title for what could be a precursor to even a suite of projects It may not be just one project, but it might be yeah, it could be a number of projects around that same theme So I've been thinking of flipping the idea of the ascent of man and calling it something like The Ongoing Ascent of Humankind so here's a regional BBC series and the book from 1973 and I think we've just gone past his 50th anniversary.

I was hoping to do something for his anniversary, the 50th, but just couldn't do it from COVID and lockdown and so on and hence another project popped up. But I've been going back to that project and thinking I could either do a book or a TV series, similar to the original one. But just flip it and rather looking at the the last hundreds of thousands of years of human evolution actually flip that and look at the next hundreds of thousands of years of human evolution.

So I have 13 chapters ready to go in some form. And that may be my next project, fantastic. And it could be a music album. It could be the book. It could be a BBC kind of a more serious kind of a series. So I'm just toying with those various ideas now and seeing where that leads me and hoping I'll wake up one morning and the inspiration will hit me that this is what it needs to be.

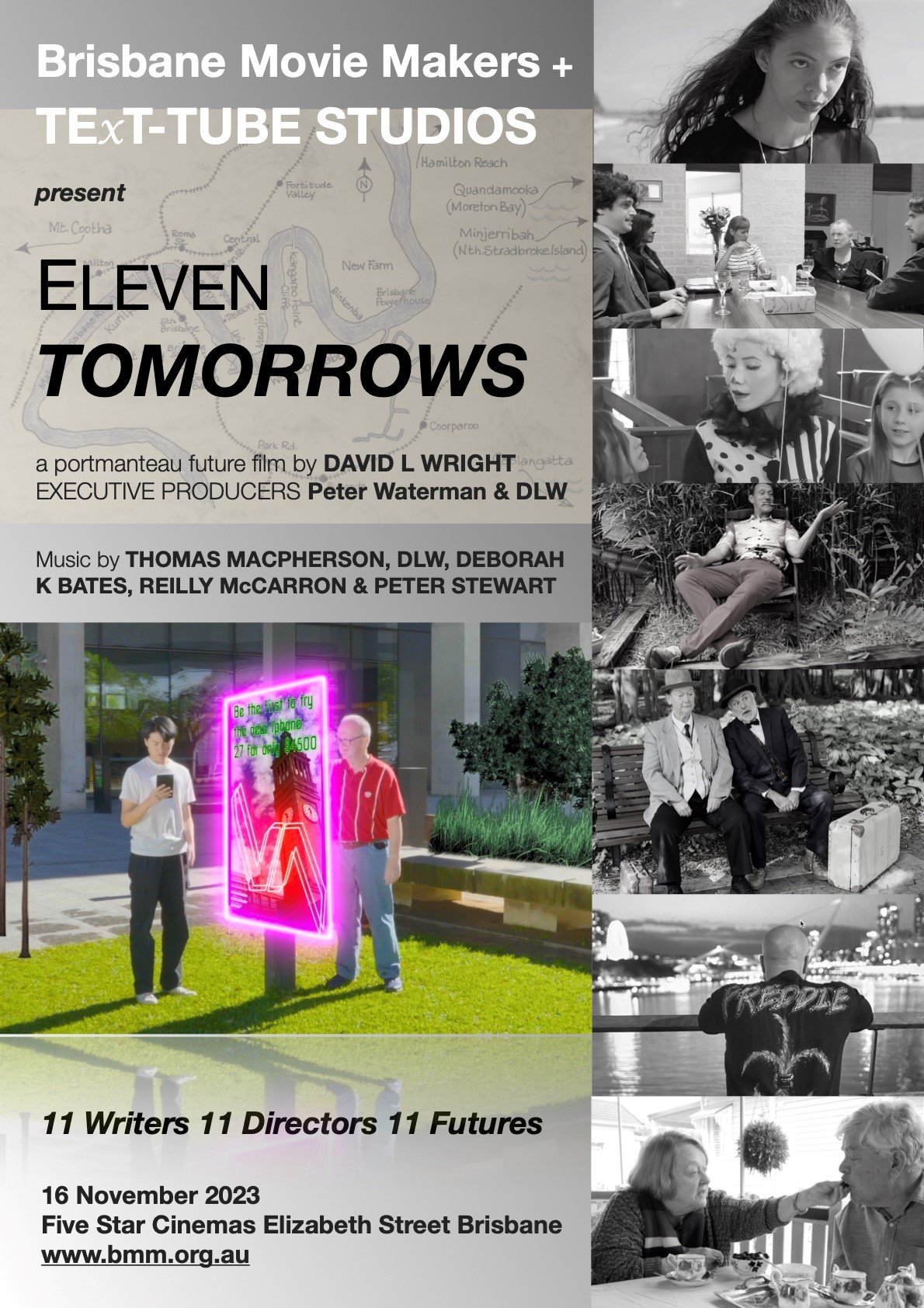

It hasn't quite got me yet, but it's getting close. I'm confident about that project and but coming back to your question, you asked me what I've been up to. So I think my big project for the last 20 months has been - it's actually a futures feature film, which we ended up calling Eleven Tomorrows.

It went from 21 Tomorrows down to seven tomorrows and 13 Tomorrows, finally settled at Eleven Tomorrows at the at the 11th minute the 11th hour, I should say. So yeah, it's a feature film two hours and eight minutes long. And basically, in a nutshell, and I'm sure you have some questions around that, it is 11 short stories or flash fictions.

From eleven writers and eleven directors and their perspectives on the Futures of the Brisbane area. That's right. It speaks to what it is.

Peter Hayward: I haven't actually watched it. There will be a link to it in the in your show notes for people watching the podcast. But I did a quick spin through it when you sent me the link and it did remind me of Shortcuts by Altman in the conversations around LA, but again, the difference being, this was people talking about the futures that they envisaged, hoped for, wished for the Brisbane area.

David Lindsay-Wright: Correct. Yeah, now, you probably know that Short Cuts by Robert Altman, there was only one director so he had quality control over all of the very short films. Unlike myself, who did not? And that can be both a good thing and a bad thing.

Peter Hayward: Again, I think, the nature of the future's work, as we know, it sits on the edge of creativity and chaos. People have idiosyncratic ideas about what they think a good or bad future is, don't they?

David Lindsay-Wright: They do. And from the very beginning, we toyed with the idea, should I have control over this? And should we have like standard camera, which is used throughout the entire film, or should we just let it go?

So we were toying with that. What's going to work best? And look, it became apparent really quickly, like in a week or two, that I'm not going to have any control over this. It's going to go, it's going to be what it is. And so we had 11 writers, directors with their own styles, their own idiosyncrasies, as you say, and probably had 11 different cameras 11 different editing teams.

So we just decided that's the way we're going to go. And we'll just see what pops out the other end. So, it was an experiment from beginning to the very end.

Peter Hayward: So can we go back to the start? So where did the idea first come from for this kind of a collection of people telling their story of Brisbane?

David Lindsay-Wright: Yeah, look, there's quite an evolution in it. It goes back, what, 12, 15 years when I was working in Japan and I developed an issue around features filmmaking and in a genre that some people call design fictions. And a Design Fiction, the idea is that you create a story around a future, which hasn't quite happened yet.

It's in progress, in development, in better form. It could be a technological device, but not necessarily. It could be a new way of doing education, or a new way of having a family, or whatever. So it could be a social technology, or a predictive technology. In Japan I created probably a thousand of these short stories with my students over, what, ten years?

And we would have little film festivals at the end of the year. And that was exciting and it felt a little bit like Hollywood. Then I came back to Brisbane to 2013 and I worked across two or three universities over here. And they were all short-term contract work, which is pretty unsatisfying, to be honest.

A few years back, and this is during COVID, I was working on a book which I was hoping to turn into a film. And I had stories that were set in Japan, a little bit in China, a little bit in the United States, a little bit in New Zealand, a little bit in Australia, a little bit in Papua New Guinea too.

And I said to myself, I'm never going to get this made during COVID, during lockdown. What am I going to do? So I started looking around from lockdown and I found this organization called the Brisbane Movie Makers. And I thought, oh, they're probably somewhere really far away from Brisbane. But as it turns out, they were literally 300 meters from where I was.

So I thought that's a sign. I can't ignore that sign. So I went to one of their evenings and, the first night I went along, they just happened to be showing some of the films made by the members of the BMM, Brisbane Movie Makers. And of the four films, three of them had quite distinct futures themes.

And I thought, here we go, come on, what am I doing here? Let's not struggle and try and make this all by myself during lockdown. We've got a team of probably a thousand years worth of experience with all these various filmmakers and some of them in work, for example, one of the directors of Eleven Tomorrows was a guy called Neal Reville and have a lot of respect for Neil.

He's mid to late 80s already, but he was an ABC sound engineer for 40 years. Wow. Anyway, back to the story. They had three films one of them was about the futures of water in the Brisbane area. And I thought, look let's just team up with these people and maybe make some kind of what they call a portmanteau film or a, I think it's called an anthology film.

Where you have various writers and various directors and it all comes together under the umbrella of a single film. So the next time I went along, I, I put the idea to them and then it went to the committee. Long story short, they said this is a good idea, this is the kind of inspiration we've been looking for.

It's going to bring everyone together and it's going to force everyone to up their game a little bit. So it was good for them, it was good for me, and clearly there was a lot of talent, a lot of people with very authentic stories to tell, and so we formed this collaboration and we launched this officially March 1 which is World Future Day, in 2022 it would have been.

Now the idea was that we would finish by March 1, World Future Day, in 2023, and As you can imagine, the end of COVID we had so many dramas, people dropping out, people going into hospital for weeks at a time. I think we had two divorces of people who were going to make films for Eleven Tomorrows, people who just lost interest, people just coming and going, new members coming in all the time.

So there was just as you said before, the this murky line between chaos and creativity and coherence and over a period of, as it turned out to be 20 months, we finally got Eleven Tomorrows done, and we had a little sequel. We actually had 13 stories, and we had to combine one of the stories, three of the stories into one.

So there you were, anyone who watches a film will notice there's a 1A, 1B, and a 1C. I saw that. Yeah, and the, there was the same actors, Tim and Therese, who are really good actors. They're actually theatre actors, and so we combined Their story into 1A, 1B, 1C and ended up somehow with 11 tomorrows.

So that's the backstory to it.

Peter Hayward: I'm going to take you a bit deeper into that just because there's, for me, I see a natural philosophical aspect to this way of letting people author their future rather than moderate it through an expert. But I'm talking to you now as a, as both a futurist and also a filmmaker that, where do you stand on this notion of the expert? Authoring, authorizing, legitimizing, or the, dare I say, amateur, auteur, from their perspective.

David Lindsay-Wright: Now it's a really important point and I, the original idea was that I would actually write and direct all eleven stories by myself and then I found Brisbane Movie Makers and thought, now this is going to be a lot more interesting.

In terms of a democratic way of looking at the future, now, for example, if you go to any city council or regional council website, you're likely to find scenarios of the future that now seems to form part of their KPIs, and that's not a bad thing, but there's a sense that they're written by people in council, for council you get a sense that nobody ever reads them, and even if they do read them, it's in one ear and out the other, or one eye and out the other.

And nothing really ever happens about them. On the other hand, from my experience in Japan, when you actually have students use futures tools, and methodologies, and techniques and theories. To actually come up with a story about something they feel strongly about that's when you get something which is really strong and authentic and heartfelt.

And the kind of story because it's also an audiovisual form, it really forces them to actually flesh out what that story needs to be or should be. And again, this is something that councils cannot do. Yeah.

Peter Hayward: So the thing that struck me, David, when I was watching and again, I have to watch the whole two hours yet, but what I saw there, and this is probably part of my crime for being an ex-consultant is that it's almost like a time capsule from the future that you could actually present to the present decision makers. To simply say, are your plans adequate for what these people expect there to be in the future?

David Lindsay-Wright: We could do that, and part of my reason for making this film was to try and achieve that. And so when I did the mailing list and tried to invite people to come along, I invited probably about 20-25 politicians from the local area.

And some of the people I know quite well, because we're on the same P& C committees and so on, I was expecting some kind of a response, but disappointingly, I only got one response, and that was actually from the Mayor of Brisbane, who did have the decency to get back to me, and there was a bit of a bit of a to and froing of communications with the Mayor, so that, that was good.

He couldn't come that particular night, because it was a bit sudden. The whole project came together quite suddenly, and so it was disappointing that, The politicians who should have a very strong interest in the kind of ideas and thoughts and scenarios and stories that people have about their own futures city ending up by not coming along and not even making any kind of contribution or any kind of even response.

You would imagine all politicians would have a really strong interest in knowing what their people are thinking. And to think that these people are actually spending hundreds, if not thousands of hours of their own time to put together a story with music and special effects and everything else involving actors and locations and not even saying congratulations that sounds really good.

Look, I'm sorry, I can't come along, but can you keep us informed? But alas, no, there was no such response from local Brisbane politicians other than the mayor.

Peter Hayward: I wonder, David. And again, I'm probably jumping ahead and it's not about your film, but given the experience of doing it and obviously put COVID to one side, but given the experience of engaging people to document audio visuals of their futures and packaging them to present back, if you had an organization that said, we actually are interested, could you commission a piece of work to do just that? Given the experience of cost and time, is it feasible to actually design something like this to an organization or a group of decision makers that actually wanted you to do it?

David Lindsay-Wright: The short answer is absolutely yes. And that's what we do with my media production company. And now that we've done this Eleven Tomorrows, we actually have a new team of quite dedicated and talented people. So the answer is yes. If somebody wanted us to create some kind of a vision of a future or futures for the particular organization or the region or their device technology or the social technology. Absolutely, we have all the skills to put together a story which would probably be based on some kind of a futures visioning workshop.

With the various stakeholders and flesh out the main points that need to be expressed in that particular story write the story and have it approved, put together the production team locations and so on. So absolutely. Again, as I mentioned before, that's what we did in Japan with students, which weren't commissioned works, but based on the things that we were doing in Japan, we actually did get some commissions from various.

Even governmental organizations and a few city councils and some private organizations who just wanted some kind of a vision of the future, which they felt that they weren't really equipped to actually visualize.

Peter Hayward: Yeah I would imagine, they could do the purpose built and if you were to, in terms of herding cats and letting a community group generate information from the bottom up is that also something that could be feasibly done? That rather than actually commission an entire piece of work, you actually commission that kind of chaotic, democratic, creative process?

David Lindsay-Wright: Ah, okay, that's, okay, now I get the question. That's a slightly different question, perhaps. And my answer is going to be slightly different. Okay, that brings me back to a project that I did start in Japan with Somebody that I think that you're probably quite familiar with, and that's Tony Stevenson, who was professor of communication and futures at the Queensland University of Technology and also president of the World Future Studies Federation for some time.

So Tony came over to stay with me two or three occasions while I was in Japan for 10 years, and we were actually working on something. This is interesting. We try to keep it secret because Tony knew that this was going to get out and unfortunately, Tony has passed away in the meantime. So there were two projects.

One was called Future-Zine. And what that was a computer graphics rendition of the island that I was stationed at in Japan, which is called Hokkaido, which is quite a big island. and a very cold island. And what that allowed people to do was to democratically go into their particular region and upload a story that they've created about the future or futures of their own particular region from some particular perspective.

So the prototype that we made, and this is going back, actually, this is going back like 15, 16 years now. We had one young lady who put. Something together about fashion features and using materials that she thought would be important from the future What else do we have we had a gang and the gang was designed to encourage young people Inspire young people to be more involved in politics because I think the Japanese young people are famously particularly A little bit indifferent when it comes to politics, they just think it's a bunch of old guys and corruptly using money and doing things that they have no particular interest in.

So I think that was called Fouris. Now, funnily enough, I just talked to the guy who designed that. About 20 minutes ago, about something entirely different. So he's a Japanese guy who came out to Brisbane to do his master's degree, and he's just living literally around the corner from me. So that was Future-Zine.

So that was one attempt to actually create a futures platform that could be democratic, democratically operated for people to upload their own stories, their own futures. Now because it was a university project and we never really got approval or funding to actually make it happen, it just sat there for years and years.

But it's an idea that could actually happen quite easily.

Peter Hayward: If you look at social media, if you look at people, with smartphones and platforms like Tik Tok and everything else, people are showing a talent, an aptitude, a desire to communicate ideas, both entertaining, but also activism ideas using digital means. There does seem to be some both technologies landing at a time where this whole generational aspect and the political aspect kind of seem to be meeting, don't they?

David Lindsay-Wright: Absolutely. That's again, that's coincidental that you mentioned that because A person from the World Future Studies Federation just alerted me last week to a piece of software called SORA AI, so SORA, S O R A which may be taken from the Japanese word which means sky. SORA as I understand is AI generated and it means you can actually input text or the spoken word and it will actually visualize that on your behalf.

Yep. Now, if you combine that with something, for example, like Michael Jackson's that's Dr. Michael Jackson, not the singer Michael Jackson, but with his software Athena which generates scenarios around certain kinds of issues. Then potentially you could actually speak into your computer and it would generate scenarios around the futures of anything that you have some kind of concern with and generate a story around that too.

Yeah. That's something we haven't quite tried yet, but that's just a matter of time. I've actually been talking to the Brisbane movie makers about that and they've asked me to. Actually present on that next week, just give a five minute presentation about the possibilities around Sora AI. So coming back to your point, yeah, that, that's the kind of software technological development, which could actually be a bit of a game changer in terms of democratizing the way people talk about the future, but also visualize stories about the future.

Peter Hayward: Yeah. Let's just go back to the 11 Tomorrows just before we close it off. Any particular stories, any things that happened in the making of it that both you want to bring up with the listeners.

David Lindsay-Wright: So one of, one of the problems that we've had is Because we're a club, we're not a professional organization. This refers back to something called Creative Cities, and this is something that you may be familiar with, and the listeners may be familiar with too, that a lot of cities around Australia, and indeed the world, have actually put quite a lot of money into promoting themselves as so called creative cities, and around the creative industries.

And Queensland University of Technology was actually the first creative industries faculty in the world. So there was a lot of fuss around this and I was involved in some of those projects too, ARC projects, and they usually involved mapping who was doing what in the creative industries. What's happened here is that with BMM, the Brisbane Movie Makers, there's the issue of actually getting, excuse me, permission to film in certain kinds of locations.

And, what's happened in the past is that some of the members have gone to city council. And said, we have this film and we'd like to shoot in Queen Street Mall or in Roma Street Park, for example, and the City Council typically respond and say, for sure you can do that. And here's a hundred page form that you need to fill out.

And you probably need a team of lawyers to help you with that. And there are so many conditions. The basically for a club or anyone who has something to say about the future. It's just basically beyond, our resources and means. So these are designed. These creative cities initiatives are really designed only for Hollywood types who actually can employ assistants to actually sit down for a couple of hundred hours and put together these grants. So the word on the street, and I'm giving a more, a way more than I probably should, what we're going to do, what we have been doing is really just not ask for permission, but we just beg forgiveness.

So anyway, we had a few of these incidences while shooting. Eleven Tomorrows, and I'll give you one example, and this was, we were shooting, we went to the Botanic Gardens in Brisbane, downtown Brisbane, at five thirty on a Sunday morning, thinking no one's going to be there at five thirty on a Sunday morning.

Lo and behold, there was almost a traffic jam in the Botanic Gardens, and we had a curve of about ten people. So we sat up there, and we had all these council workers mowing the lawns and coming right up to us, and they just sit in their mowers. And we thought they were going to come up and say: Where's your permits?

But they never did. They just backed off and they disappeared. And we kept on shooting. And we had this one last shoot to get. Which involved Tim and Therese and an extra in period piece, because it was about the history of Brisbane, referring to the futures of Brisbane. And we just got this one last shoot, we had a clear run, there was nobody coming, no joggers or anything, no one on a bike swearing at us.

We had a few people doing that, going through and starting swearing at us. Just as we were about to turn on the cameras I could see just going through QUT grounds, there was like three police officers. This is now like 6, 6. 30 in the morning and I thought, oh no, here we go. Anyway, they're about 100 meters away from us looking through the trees and they actually stopped and started pointing at us.

It was like something out of a Mr. Bean movie. It was just it seemed so contrived and I thought they're going to come down the stairs because there was a staircase just there. Anyway, they got to the staircase. Incredibly, they stopped at the staircase, and then they just kept on walking. They never came down to us.

And the shoot went on, and incredibly, almost a miracle nobody disturbed the shoot. We got a perfect shoot. Perfect lighting. The lighting was absolutely perfect. The sound was brilliant. The cops never came down to us. That's where our permits were. And it all ended up just really nicely. So that was one example.

We had a few of those examples too. In other films as well, with the police actually showing up and sitting in their car, watching a shoot and thinking, are they going to come over and shut the whole thing down? But they never did. Wow. Again,

Peter Hayward: It's a funny anecdote, but it is a real issue, isn't it? If we do want to democratize people participating on the ground in real places, then where you bump into bureaucracy, security. And everything else. And it is a challenge. I don't know, obviously you aren't going to advise people to break the law.

David Lindsay-Wright: Yeah, it's a bit of a grey area. But the BMM, the word on the street there, BMM, is that we're never going to get permission because it's just, there's just so much paperwork and it ends up being quite expensive because you actually need to employ people to come along and cordon off streets and things like that and, if you are Taika Waititi and you're shooting Thor in downtown Brisbane and you've got five assistants and you've got 80 million to play with, sure, you can deal with that.

But for people like ourselves who are doing this on a shoestring budget of 30, 000, by the way, I will mention the budget for the Eleven Tomorrows was 30, 000 for a two hour and eight minute film, which we actually calculated, interestingly, We compared that, how much would that make of the world's most expensive film, which was Star Wars - The Force Awakens, which was made on a budget of 447 million.

I think I calculated that the budget that we had would make 0. 25 of one second of that same film. So you can imagine these are the kind of odds, but. This is really important because if you want people to actually be involved in the creative industries film, music and so on, there needs to be some kind of allocation for people who actually don't have budgets, which in the creative industries is pretty much everyone.

What you're saying is we don't want anyone local to make a film or a concert on a low budget. We just want Hollywood people to come in here and then you've got Taylor Swift and then the whole country goes mad kind of a thing. And I just want to make a point about that because there are so many films about the future made on just massive budgets.

And man, so many of them are so bad. The production quality to be sure, is just impeccable. Extraordinary. And even I look at some of those films and think, how do they make that film? That the production quality is just extraordinarily high. But at the end of the day, you walk out and think I didn't really learn anything from that.

And you go home and you feel nothing better about the future or anything else. Whereas our film's made on a very small budget and you've got 11 people who feel strongly about their films and their stories and their ideas and their themes and concepts. But at the same time there's just not that much interest cause it's not made on a budget of a hundred million dollars.

Yeah. And this is a real pity, but from the point of view of a futurist such as yourself and your listeners. I think that the Eleven Tomorrow is the kind of film that actually is pretty interesting. And if you can go past the production quality and look at the ideas, then hopefully that will spark some interest, some inspiration.

And you can imagine what you could do if you had about a hundred million dollars to play with. I've been thinking about that, but I haven't got a hundred million dollars to play with.

Peter Hayward: So what, in terms of the project, the film is out on YouTube and as I said, the link will be. In your show notes, but what's next for the project? It's still got some life in it for you. I believe

David Lindsay-Wright: it does. And we've been toying with the idea of doing like a second, maybe a third screening at a separate cinema. And that's something that we may do. And I'll keep you informed about that. We've had quite a bit of interest from other countries. Who think this is a really good idea.

This is the kind of thing that we need to do for our country. And some of those countries include Papua New Guinea. And I have a good friend who's a friend of the Prime Minister. And we met with him just before COVID hit. And that was before we had the Eleven Tomorrows idea. But the Eleven Tomorrows has now gone to the Prime Minister.

And we're just waiting for the vote of no confidence and for PNG to settle down a little bit. It's in some turmoil right now. I've got a friend who's a filmmaker in New Zealand and he's taken this to a couple of cities over there. Who trying to be recognized as UNESCO Creative Cities, and he thinks he may get some tread over there, some stickiness over there.

So there is some talk about doing a franchising kind of an idea where the idea of Eleven Tomorrows Could be taken to any region in Australia, and basically it would be like some kind of an open invitation a form of user generated con contents, or user generated story filmmaking, where you designate six months or three months or a year and you get back five films or 20 films and you have some kind of like a public forum and a panel discussion with the filmmakers and the writers and you sit down and watch the film and you answer questions and have a discussion and potentially open up some kind of a discussion and debate about the ongoing futures of your particular region.

That's where we're going with Eleven Tomorrows, so it's not going to go away for some time, I believe. Now whether that has any sort of commercial potential, that is something a little bit different. I think that it does, but we just got to let it go loose for now, and just see where it lands, and If anybody listening has any background in literary studies, this is called traveling theory, I believe, which means that you write a book or you print a T-shirt and you just let it go and just see where it lands over time and space.

And you never know, the idea could be picked up by somebody completely unexpected, unanticipated. In a region that you haven't really thought of, so that's what we're doing for now. But in the meantime, I have toyed with the idea of actually sitting down and going back to my original idea of three to four years ago.

And actually using a more kind of systematic methodical approach to writing stories about not just Brisbane, but potentially in any place in Australia. And writing those stories for a start the way I envisioned that they needed to be in the first place. That's another potential project.

Yeah. And there is one other story too. One other possible spin off idea. And that came from. The director of one of the stories in Eleven Tomorrows, a guy called Glenn Bruce, who's a primary school teacher. He wrote and directed the story called A Matter of Choice, which was a very real story and it was about the problem of real estate in Brisbane, which is a real problem … which causes a family death, I won't say too much because it's, it could be a bit of a spoiler.

But Glenn came up with the idea that why don't we actually have a documentary, a non-fiction version of Eleven Tomorrows. And, for anyone who sits down to watch the movie, they will notice that of the eleven films, 10 of them are fictions and dramas, but one of them is actually documentary and that was by Nigel O'Neill and and Paul Michaels.

And that was about the issue of transportation, which again, is a very real issue in Brisbane. So there's one documentary and there's 10 drama fictions. So the idea was why don't we sit down and actually take 10 or 11 issues of real concern to Brisbane and actually make them into an extended portmanteau documentary film.

There's another possible idea as well, too. Cool.

Peter Hayward: I'm gonna start off and congratulate you on achieving the 11 Tomorrows, certainly you and the Brisbane movie makers did a great job, so congratulations on that.

David Lindsay-Wright: Thank you Peter, I appreciate that.

Peter Hayward: I think your ideas, it just struck me that your ideas in Japan for what you and Tony were talking about. Way, way back then, and now the technology that's in people's pockets. It just seems that the gamification aspect as well as the kind of digital, it would seem as though, people are going to use technology and their own innate sense of what they want, that they're going to do it whether we encourage it or we don't.

David Lindsay-Wright: Absolutely, and of course that's already happening around new technologies such as Chat GPT and so on, and all the variations around that. I think it was I think it was William Gibson who said that technologies find their own use on the street and for better or worse there's no way to control them.

Once they're out there, they're out there and they will keep evolving in their own way and hopefully for the better and sometimes, unfortunately. It won't be for the better.

Peter Hayward: Thanks. Thanks for taking some time out to spend some time with the FuturePod community and hope to catch up again in the future.

David Lindsay-Wright: My pleasure, Peter. It's been really good talking to you and appreciate your interest. It's well noted and I will get back to Brisbane Movie Makers and report on this podcast and hopefully they'll get to listen to it at some time in the future too and look forward to talking again. Best of health to you and let's talk sometime in the near future. Absolutely. Okay. Thank you again, Peter.

Peter Hayward: I do hope you'll take the time to watch 11 Tomorrows and please pass it freely amongst your networks. If you are a community decision maker or working with one I hope you will considering engaging David or employing his approach in doing your futures work. I'm sure David would be more than willing to discuss that with you. FuturePod is a not-for-profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support the Pod, please follow the Patreon link on our website. This is Peter Hayward. Thanks for joining me and see you next time.