Sarah Dillon is Professor of Literature and the Public Humanities in the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge. Dr Claire Craig is Provost of The Queen’s College, Oxford and has extensive experience of providing scientific evidence to senior decision-makers in government and business. Together they have written Storylistening. In it they provide a theory and practice for gathering narrative evidence that will complement and strengthen, not distort, other forms of evidence, including that from science.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

More

Website: https://www.storylistening.co.uk/

Social media: @profsarahdillon on twitter

References

Belton, O., and Dillon, S. 2021. ‘Futures of Autonomous Fight: Using a Collaborative Storytelling Game to Assess Anticipatory Assumptions’. Futures 128, 1–13. DOI: 10.1016/j.futures.2020.102688

Bisht, P. 2020. ‘Decolonizing Futures: Finding Voice, and Making Room for Non-Western Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing’. In R. Slaughter and A. Hines (eds.), The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies 2020, 216–230. Washington, DC: Association of Professional Futurists.

Burnam-Fink, M. 2015. ‘Creating Narrative Scenarios: Science Fiction Protoyping at Emerge’. Futures 70, 48–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.futures.2014.12.005

Candy, S. 2018. ‘Gaming Futures Literacy: The Thing from the Future’. In R. Miller (ed.), Transforming the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century, 233–246. London: Routledge.

Eggers, D. 2010. Zeitoun. London: Penguin Books.

Fergnani, A., and Song, Z. 2020. ‘The Six Scenario Archetypes Framework: A Systematic Investigation of Science Fiction Films Set in the Future’. Futures 124, 102645. DOI: 10.1016/j.futures.2020.102645

Kahn, H. 1960. On Thermonuclear War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kingsolver, B. 2012. Flight Behaviour. London: Faber & Faber

Le Guin, U. 2015. The Wind’s Twelve Quartets & The Compass Rose. London: Gollancz.

Pohl, F. 2012. ‘The Future’s Mine’. In N. Harkaway (ed.), Arc 1.2: Posthuman Conditions, [n.p.]. London: Reed Business Information Ltd. Kindle DX Edition.

Robinson, K.S. 2015. Aurora. London: Orbit.

Schwarz, J.O. 2015. ‘The “Narrative Turn” in Developing Foresight: Assessing How Cultural Products Can Assist Organisations in Detecting Trends’. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 90(B), 510–513. DOI: 10.1016/j.techfore.2014.02.024

Schwarz, J.O. 2020. ‘Revisiting Scenario Planning and Business Wargaming from an Open Strategy Perspective’. World Futures Review 12(3), 291–303. DOI: 10.1177/1946756720953182

Shute, N. 1957. On the Beach. London: Heinemann.

Transcript

Peter Hayward

Hello, and welcome to Futurepod. I'm Peter Hayward. Futurepod gathers voices from the International field of Futures and Foresight. Through a series of interviews, the founders of the field and emerging leaders share their stories, tools and experiences. Please visit Futurepod.org for further information about this podcast series. Today, just for a change, we have a pair of guests, Sarah Dillon and Claire Craig. Sarah Dillon is Professor of Literature and the Public Humanities in the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge. Dr. Claire Craig is Provost of the Queen's College, Oxford, and she has extensive experience in providing scientific evidence to senior decision makers in government and business. Together, they have written Storylistening. In it, they provide a theory and practice for gathering narrative evidence that will complement and strengthen, not distort, other forms of evidence, including evidence from science. The book explores where decisions are strongly influenced by contentious knowledge and powerful imaginings, examples include climate change, artificial intelligence, the economy, nuclear weapons, and power itself. It focuses on the cognitive and collective functions of stories, showing how they offer alternative points of view, create and cohere collective identities, function as narrative models, and play a crucial role in anticipation. Welcome to Futurepod, Sarah and Claire.

Claire Craig

Nice to be here, Peter.

Sarah Dillon

Thank you for having us.

Peter Hayward

It's a pleasure. So you said you've heard a couple of Futurepods. So you know that the first question is the story. So what is the Sarah Dillon and Claire Craig story? How did you get involved in and end up writing a book called Storylistening?

Sarah Dillon

That's a good question. Sometimes I wonder how it happened. I think we met – Claire can correct me if I've got the date wrong – in 2017, I think, when Claire was involved in setting up a wonderful project on AI narratives, so the stories around artificial intelligence, how they inform public perception, decision making, the science itself. And I was very lucky to be pulled in on that project, because of my love of science fiction, and my interest in the intersection between science and literature. I'd also been doing for some time quite a lot of public work broadcasting with the BBC. I was very interested and keen to think about how the kind of work I do in the literature department can take itself out to other places and be helpful and useful in other environments. So we met there. And of course, Claire was already at that point, quite well established in Futures – weren't you Claire?

Claire Craig

I don't know about that, but carry on.

Sarah Dillon

And so we went on that project for a while. And then we were at a big event in London, and we were sitting having a drink. And Claire said: shall we do something together? I was like: yes, we should do something together. So I said: shall we write a little book? And four years later, after all other projects had then been abandoned, the little book is about to enter the world, and it's not so little anymore. So that's my version. Do you have a different version? Claire?

Claire Craig

No, no. I mean, it was fantastic, to be honest, because, for me, at least, this sort of sense of – I mean, way back I worked in science advice, particularly advising the British government, and I worked for part of the time on a project on a program called Foresight, which some may have heard of. For a long time, I began to feel the kind of lack of, or the difficulty of, bringing in all sorts of humanities knowledge. You know, you spend millions, hundreds of millions of pounds on your computational model of the climates and then kind of leave it to almost to the politicians have free rein in terms of what that might mean for publics and society. So finding somebody from the humanities side that actually wanted to talk about this problem was brilliant. And then, like so many, I think, I know that I've learned a lot from listening to stories in my life and I wanted to make sense of that as well. So it's been a fascinating journey. And of course, having to complete the book during the pandemic, which in fact, was perfect. Because we were separated, we could work really seamlessly. I mean, at time to the kind of hive mind, hive brain writing the book at the same time, which we couldn't have done a few years ago.

Sarah Dillon

Yeah. We're well used, Peter, to talking to each other through the computer – we've spent many, many hours, as you know. In fact, we went a good full year and a bit without seeing each other in person at the most intense period of writing the book.

Peter Hayward

It's not just the literature and just the humanities, but it's that ability to actually make it meaningful for really the broader community need. Has that always been something that's been with each of you or something that has grown through your career?

Sarah Dillon

That's a really good question. Obviously, when you start out as a PhD student, you're just narrowly focused on, you know, your discipline and mastering it and making a contribution to it. But as I moved into a job and started to do some radio work, and other things, it became almost a matter of urgency to me that I thought about how what I did in my relatively narrow sphere could have consequences and impact elsewhere. And I had met that need through doing the broadcasting. But I had started to realize I wanted to take it into other areas, like policy and decision making, where I wasn't seeing the kinds of knowledge and the kinds of evidence that that my discipline and the humanities produce. There was a desire to take it seriously and incorporate it, but a lack of framework and understanding on how to do so. So that was where my urge to do it came from. And that was why meeting Claire, who has extensive experience in that sector, was really important. It's also been a big learning curve, because I've always been the one with the humanities academic hat on making sure everything is rigorous according to humanities principles. And Claire, whilst entirely supporting and ensuring we do that, has also always been reminding us that we have a practitioner audience, and we have to write and speak and communicate in ways that get our message across to them. It's been quite difficult to do that in a single monograph. And I think in the end, the balance shifted towards having a book that was really rigorous and provided a good theoretical foundation. And then it's really important to us – and Claire might want to add to this – to then do lots of things, like this wonderful podcast, around the book that help to translate it, so to speak, into different languages for different audiences.

Claire Craig

To me, the answer to your question goes back to when I was I was a postdoc. I did a PhD and I was doing research in geophysics. And I had some colleagues who were doing seismology. And it was one of those kind of defining moments for me: when they did a small paper – they were studying earthquakes in Greece and Turkey – and it showed that the size of the earthquake was less important to how many people died, than the building materials that were used locally. So, I thought: gosh, I could spend my life working out, sort of, slightly more fine detail about what earthquakes were like, or I could kind of get out there and start being involved in building regulations. I haven't actually been involved in building regulations. But I had a bit of that sense of urgency. And then spending a lot of time working on science advice in government, which, of course, has become much more visible in many countries during the pandemic, and the mechanisms for it have also become more visible. But you know, it's just like there's so much knowledge in research in all disciplines that just doesn't get to the decision makers and the publics in the way that it could, because the incentives on researchers are to be good researchers. Which is fine, but it then means that there's a kind of time lag between knowledge being created and it being used to inform either immediate decisions – what we're sort of more evolved to talk about here – or it being involved in shaping and informing anticipations. So I got really interested in that gap and how to make that gap, between the knowledge that exists or could exist and decisions and debates that influence the world now and in the future. You know, how you can build bridges across that gap, and Storylistening is part of that.

Peter Hayward

With the narrative turn and the pivot into the actual humanities and literature as a way to, if you like, structure or support decision making – and it strikes me as odd given that, in the past, particularly political leaders, and particularly in England, I'm thinking of people like Disraeli and Churchill, were actually writers as well as political figures. And I'm not saying that their writing was part of their political strategy, but they definitely were comfortable and communicating through humanities and also taking a policy leadership role. Which kind of begs the question of, are you returning or reinforcing things that we used to do? Or are you in fact bringing forward a set of capacities that are really novel?

Sarah Dillon

That's such a fascinating question. I mean, I can answer it a little bit in thinking about the humanities. But Claire, actually, I've never asked you this in terms of your knowledge of the history of the types of evidence that's been taken into account in decision making, and when scientific evidence became or was the dominant form. Did you know that? Sorry to put you on the spot, but I'm really curious. Do you know about that history?

Claire Craig

I don't think I do, in any useful way. The British Academy has done a little bit of work on how on how policy has been formed in the past. But I think, to be honest, that part of the key answer to Peter's question is that what he's talking about, may be more about storytelling than storylistening. One of the things we try to be clear about or make a distinction about in the book is that there is quite a lot of thought about telling stories, including actually advice to scientists on, you know, you must tell a story about your work, and politicians obviously are good at telling stories. What we're interested in is listening to stories and the skill of listening to them. And that's a much less observed and interrogated activity.

Sarah Dillon

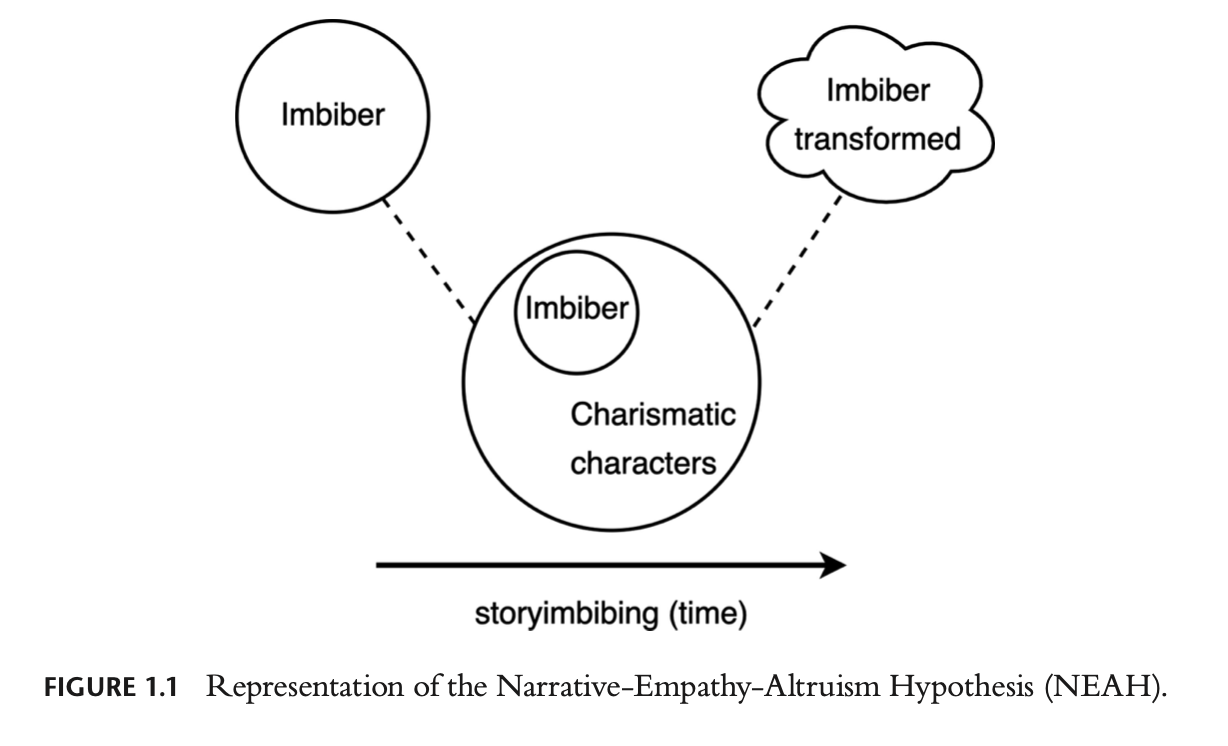

Yeah, and the other thing, I mean, to give a contemporary example to your Disraeli and Churchill: someone like Obama is very well-read and publishes his annual list of favorite books. And one of the things we're also trying to get away from in the book is the idea that, if only all politicians – or futures practitioners – read more stories, they would be more empathetic and wiser, and make better decisions. That's just not an argument that we're interested in making. One, because we're interested in listening to stories and their functions and effects at collective levels, so not their influences on elite individuals. But also because we spend the first chapter arguing against the idea that engaging with stories makes you more empathetic. And that actually what it does is to offer multiple different points of view on the system that you need to be thinking about in relation to the decisions that you're making. So we're very much moving away from that kind of charismatic figure, and his or her engagement with stories, to thinking much more about about the collective and the collective impacts.

Claire Craig

And there will be something in the historical evolution that you're talking about, from Disraeli, to do with the disaggregation of disciplines, the specialization within disciplines. So the number of researchers has gone up dramatically and continues to go up pretty rapidly with increasing wealth around the world. And the specialization within disciplines increases. So the risk of public debate and decision making being informed only by one sort of evidence – notoriously economics, certainly at the end of the last century, and in fact, even today, the UK Government Chief Scientific advisors were saying that economics rules in British political life, in terms of forms of evidence. Well, Disraeli probably knew more people or could more easily access knowledge that integrated different forms of evidence. And so there's something about the fact, not that they could tell good stories, but that they would have been in a world where the kind of integration of thinking across different forms of knowing was easier to do, at least for the elite, because of that more integrative thinking. And one of the reasons we like storylistening now and think it's so valuable is that stories continue to be a way that moves across – you can tell a story or listening to a story which has climate change in it. And it can include evidence about the physics, but it also includes evidence about how society might live or how people might live collectively. And maybe that is going back 100 years, in a way.

Peter Hayward

A question to talk to the listeners at the level of not teaching them, but to kind of lay down some sort of fundamental theories and principles and approaches that are essential to this notion of what you're talking about.

Claire Craig

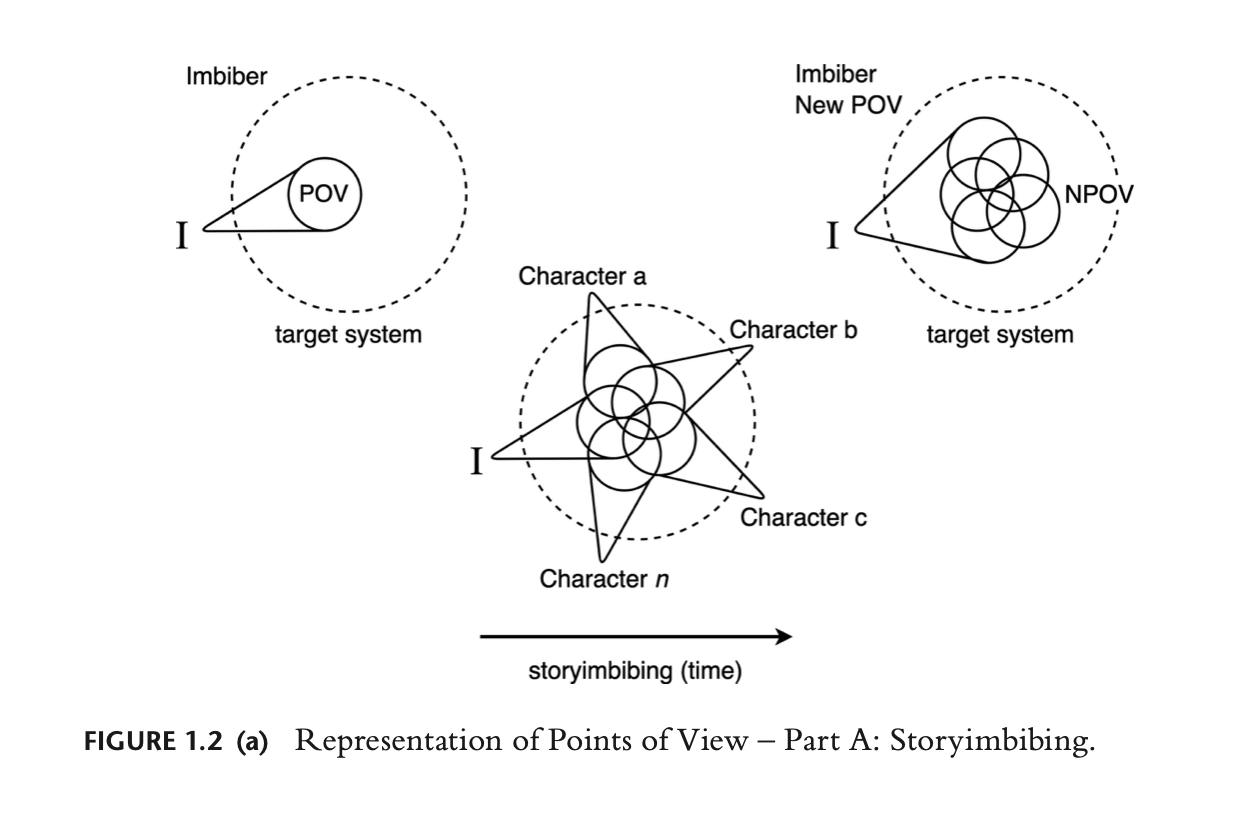

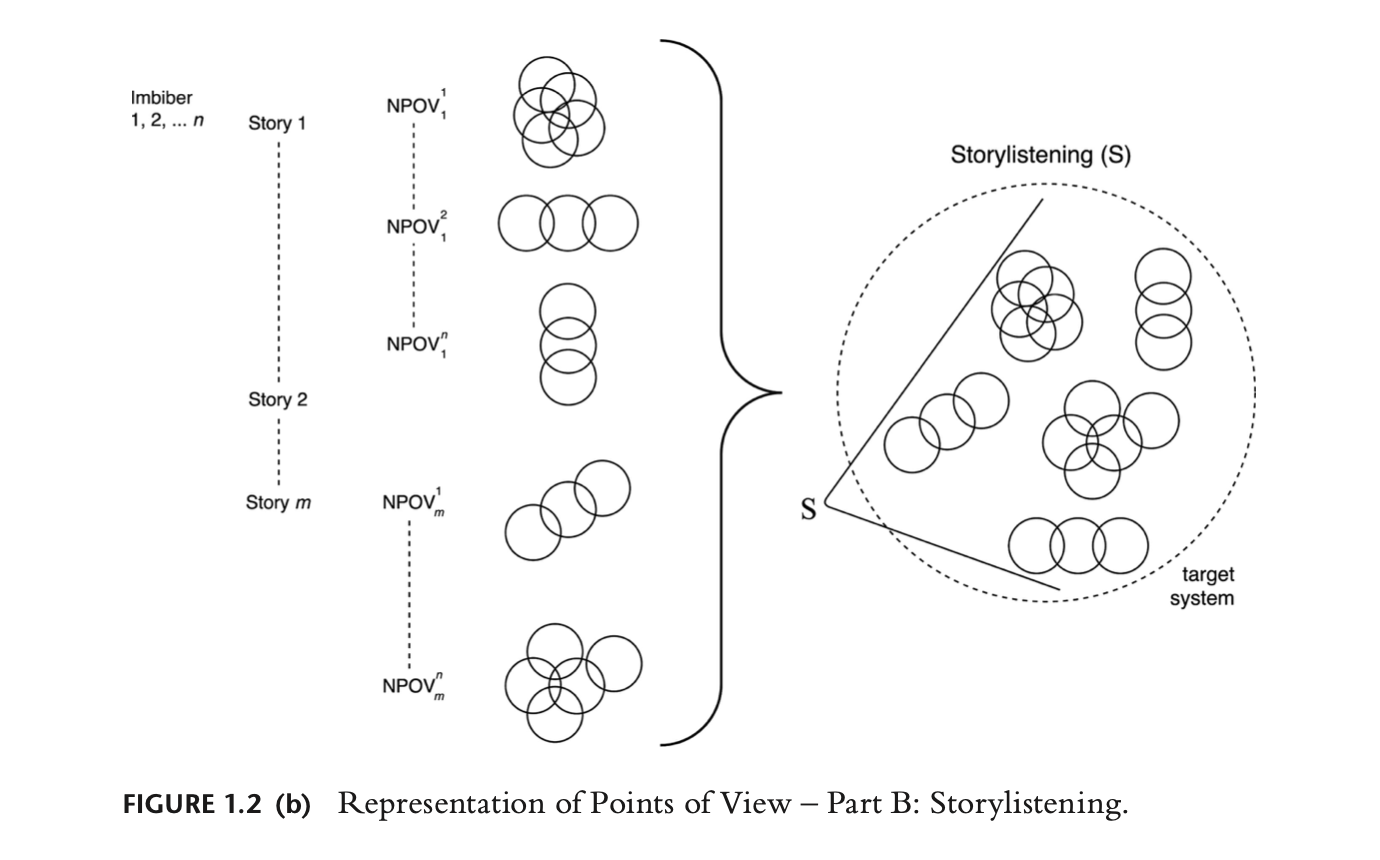

I'll do a very brief overview of storylistening and then Sarah is going to talk more about anticipation. So briefly, what we've tried to do is make it easier to integrate, include storylistening into debate and into advisory systems by introducing four functions of stories. So these functions are cognitive – we're not talking about empathy and emotional effects, important as those are – and they're collective. So, as Sarah said, we're not thinking about how one story impacts on one individual, but more collectively. And the four functions are around points of view and perspectives. That's the first one: the way that a story will convey information or evidence about the system that it is describing, that it is containing, with multiple points of view. So if you take an Ursula Le Guin short story called 'The Direction of the Road', which is told from the perspective of a tree, and it's a different take on what what cars on roads look like. Or a story might have four or five points of view about the same matter, and you can draw those out by critically listening to the story. That's one.

Another is the way that stories are connected to or create narrative networks. So people sharing stories are themselves creating or being part of a network, because of that sharing of the story. Sometimes it doesn't matter what the content is. So an anti-vaxxer group is connected by stories about the harm from vaccines, or misinformation about harm the from vaccines, and they're still connected, even though the content may be flawed. On the other hand, some stories are really powerfully enabling new insights into climate change, or whatever it might be. So the second function is around collective identities.

And then the third is modeling. The classic for me is if you read novels of Jane Austen, you come away with some model of middle-class life in Regency England. You think you know the rules of the game a little bit about marriage and social advancement. The same is true for many other kinds of stories: that they convey, that they embody models for the way the world might work. So Kim Stanley Robinson's Aurora is a model of a society and a zero waste, zero carbon world. It happens to be on a spaceship, but it's very thoroughly and completely imagined and described.

And then the fourth function is anticipation. So it's: points of view, identities, modeling, and then anticipation. But Sarah, do you want to talk more about anticipation?

Sarah Dillon

Yeah, absolutely. So whereas we perhaps don't know, and we'll find out more about the history of evidences, as per your last question. I did delve into the history of the connection particularly between science fiction and science fiction studies – what Frederick Pohl calls, when he's recalling his time in the 20th century, futurology, which I guess you might think of as the ancestor of what we now think of as future studies. And what was really fascinating about tracing that history was the absolutely intimate connection that there was in the mid-to-late-20th century between science fiction and early futures studies. So you know, Pohl, was already doing talks on the Futures circuit when he heard about RAND, and he flew straight there and talked to people who did DELFY. And he and Arthur C. Clarke went to World Futures Studies society events. He said that there was what was called a friendly symbiosis between the two. And then something happened – and the details of that something happening, I think, still needs to be written) where the two sort of parted ways. And when I looked at – Peter Bishop and co. have a great kind of overview of futures studies techniques and methods. And when I looked at that, you know, stories are there in a lot of the established methods in the field so that they're in incasting, backcasting, future mapping, science fiction prototyping, storytelling games – and we've sort of gathered all those together and called them narrative futures methods. So existing futures studies methods and techniques that incorporate stories or storytelling in some way. And we're not the only ones to identify this. But what we saw was missing where the gap was, was bringing science fiction and science fiction studies back in again, and recognizing that another narrative futures method could be one that involved using and reasoning from existing stories that exist in the speculative tradition.

And using and engaging with those stories is what we call anticipatory narrative models. So to take Aurora again, if you're thinking about Kim Stanley Robinson's Aurora as a narrative model, and you're looking at climate change, it's a narrative model that pertains to the situation we're in now. But if you think of it as an anticipatory narrative model, then the interesting bit of the book is the AI, which controls the spaceship and is interestingly self-reflexive about its role and responsibilities in relation to governance of the human population. So there you've got a very interesting, anticipatory narrative model about what it means to incorporate a sentient AI. But you can reverse that slightly and even just think about machine learning systems in the governance of human beings. So again, you've got some very interesting narrative or literary thinking there which could inform decision making about AI moving forwards. And there are other people who are making this kind of argument. Jan Oliver Schwartz is doing it; Michael Burnham-Fink is doing it. There was a great essay in Futures early last year in 2020, by Alessandra Fergnani and Zhaoli Song, making the case that we need to incorporate and bring back in science fiction into future studies and need to take it seriously and learn how to do so. And that's one of the arguments that we're making in that anticipation chapter.

Peter Hayward

What I'm hearing is that futures has always had a relationship and a reliance, if you like, on science fiction, imagining, creative narrative – that kind of thing. What you're asking the practitioners to do is to actually rather than just read them as stories, and have the normal emotional reader response to the story – exciting, don't like it, you know, whatever. But you're actually taking a stand on literary constructivist interpretation of trying to break stories down into particular aspects that unless you read for them, you may will miss them. Have I got it somewhat right?

Sarah Dillon

I think there's different kinds of listening or reading so there's reading or listening or in or we talk about storyimbibing to cover engaging. Well, we like reading, but it doesn't work if it's about a film. But viewing doesn't work if it's about a novel. So we talk about storyimbibing: taking stories in whatever medium they happen to be embedded in. That can of course be done purely for pleasure and affect, emotion and joy and escapism, and all the wonderful reasons why human beings have told stories and imbibed stories throughout our existence as a species. But that doesn't mean that they don't also have – and this is a really important term for us – cognitive value. And maybe this is a different type of imbibing, but recognizing that we also read stories to learn. They're a form of sensemaking; we get information from them, but we also organize information about the world through them. And taking that bit of stories seriously is really, really important and doing that also collectively, so recognizing that this isn't about necessarily individual readers, as Claire's been saying, but networks of story imbibers. So one of the things I did in practice was, I met Riel Miller, when Claire and I were invited out to Örebro in Sweden to an AI and anticipation event, and as a result, ended up doing a story listening workshop at the Futures Literacy event in Paris in December 2019. In fact, my last trip abroad before the world shut down, and actually it was another Ursula Le Guin story that I used there, but this time, 'The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas'. We got into groups and we collectively read it. And we thought about what that might mean for our understanding of economic systems, and if someone has to suffer for a collective good, and what decisions you make about your involvement or not within those economic systems. And so I'm sure everyone – I hope – in that workshop also very much just enjoyed the story. But I guess you're right in the sense that then we were thinking about it differently to if we'd all just been, you know, snuggled up on the sofa at home, reading it for pleasure.

Claire Craig

Sarah mentioned we met at work – actually at the Royal Society on AI narratives – and one of the real urgencies for me was that we were doing this incredibly thoughtful work about AI and machine learning with lots of scientists, people like Demis Hassabis from Google DeepMind, you know, absolute leading scientists. And of course, every time the Royal Society said or did anything about AI, it would be reported in the kind of mainstream media with pictures of the red-eyed robot from the Terminator. People tended to have three views. One was that it was completely irrelevant – didn't matter, because everybody knows the difference between facts and fiction. At the same time, some people – and even the same person at different times – would say: oh, my goodness, this is really dangerous because it is actually distorting anticipations of AI because it's focusing on the humanoid and the malign, you know, and therefore it's a dangerous direction of anticipation, because it's sending the wrong signals. And actually humanoid AI is a long way off, and it's not worth thinking about. So either it doesn't matter, or it matters and it's bad. And then very occasionally, people say, well, it's a kind of figurative, this unstoppable force; it's actually about big tech or it's about government. And it was so sort of strange in a way that there was all this effort going into the careful analysis of where to start – what science was and where it was going. And yet nobody was really taking seriously the question about these other stories, which most people thought are quite powerful, that are circulating, and what kind of anticipations they might be bringing and what we could understand about them. Not whether we like the Terminator – it's a darn good movie in my view. But it was what it means and why it mattered or how it matters and it was this critical listening gets you beyond that 'do I like the movie' into if there's something here and of course then you're forced to recognize that the villain is Skynet, which is a distributed system – the real villain. And actually distributed systems are much more important to think about in public policy terms at the moment than humanoid AI because one exists and the other doesn't.

Peter Hayward

Riel on the podcast has said a number of times – I've had him on a couple of times – that we actually, in terms of what he called futures literacy, he says we are culturally impoverished. We don't have a rich source of literacy to draw from. And part of what he's been about and promoting is this process of enriching our resource upon which we will build our literacy for anticipation, given uncertainty and technology and everything else.

Sarah Dillon

Yeah. And we talk about narrative literacy, which we should have a chat with Riel about how futures literacy and narrative literacy connect, because I think they do connect in very interesting ways. And he himself has talked in some of his writing about being futures literate being comparable to being a very good reader, actually in one of his essays. But where we're talking about narrative literacy, it means, as Claire's been saying with the Terminator, being able to understand how stories function, and in what ways, and so not simply being, I guess, at the mercy of them, but being able to stand back and be critical and be reflective. And that's a really important skill today, especially with everything that's going on about post-truth and misinformation. Storylistening and narrative literacy will give every citizen, every public a way of not being buffeted in that storm, but getting control and being able to say, how is this story functioning? What effect does it have? Is it metonymically legitimate, which is another term we use? No, does it represent a legitimate whole? And therefore, is it quite a good way for me to understand that whole, or actually is it totally distorting what's actually going on, and therefore I need to imbibe it carefully. So that would be a kind of interesting relationship to futures literacy.

Where I guess I disagree with Riel a little bit, is that we're not that culturally impoverished. We have – and I'm questioning the 'we' as well. You know, who's the 'we'? Is that me and Claire sitting in Britain? Or is it in the world? But the world is full of amazing imaginings, be they embodied in futures practices, in existing novels or films, or oral storytelling. And so it's perhaps – and we talk about this – recognizing that there are areas where we have what we call narrative deficits. So areas where there are lacks, and one of these might be, for instance, positive imaginings about the future in the face of the climate crisis. But there also might be perceptions of narrative deficits, because actually people haven't been looking in the right place. And dominant stories are overshadowing really important other stories, be they indigenous stories in relation to climate change. And so the onus there is to look for where the rich imagining is happening, that isn't yet being listened to or heard, as well as it should be or needs to be.

Peter Hayward

Excellent, thanks.

Good question. The one where I get you to put in your expertise in storylistening, just for the moment and respond about what is emerging, what has been emerging, what have you been paying attention to emerge, that has kind of energized and impelled you to move into this work?

Sarah Dillon

I mean, in a way, it doesn't get away from the refrain because what's been engaging me is where and how stories are already beginning to be taken seriously. And where actually we felt that there was a real need and hunger for a framework and a theory and a practice that could help people do that rigorously. And particularly this has for me been also areas where, and this this links to what I've just said, where stories of people who might not ordinarily have been heard are becoming attended to. So Pupul Bisht's chat with you on this podcast was wonderful to listen to and the work she's doing and using, you know, non-Western storytelling methods as a as a futures practice. There's also, for instance, the Arizona State University has a very interesting Center for Science and the Imagination. And they have just appointed some climate fellows to try and create and tell different and perhaps more positive stories about the future in relation to climate. Or I was asked to go to a workshop hosted – I think it was the Royal College of Engineering in London a few years ago – on AI and gender, and then the number of times stories and narratives and their role in determining who went into the profession who stayed in AI research, who left, how decisions about datasets were impacting on different people – stories were ever present in that that day of brainstorming and thinking. So, for me, it's recognizing that there's a shift to understanding that we need different ways of understanding the world. We need them still to be robust and rigorous. But we need to recognize that there's different forms of knowledge for different objects of things we need to know about. And so seeing all of that, and recognizing that then hopefully we could make a contribution, offer a framework for how to do some of that, has actually been really exciting.

Claire Craig

This conversation is also making me think that some of this urgency, again, thinking a little bit back: I came into science and government when climate change was still conceived as a single issue. And I don't think it's complete – I think it's very unprovable – but almost in the minds of physical scientists, because the world have got together and you know, filled in, broadly filled in the hole in the ozone layer that was, you know, coming from CFCs. And because perhaps even because nuclear war has not happened – then – yet – in the kind of catastrophic ways that had been imagined by people like Herman Kahn at RAND, or in some of the novels of the 50s and 60s – On the Beach and all that – there was a sort of sense that if you told the terrible story loudly enough, you would avert the bad things happening. And I think, within government and with many other scientists, living through the realization that that wasn't going to work in that simple way for climate change. That it was so pervasive at every geophysical scale and social scale that it wasn't a story, so much as many, many, many stories and many, many models. And that the global models just have this huge gap between what they could say about global average surface temperature, and who's ever noticed what global average surface temperature is, you know, it doesn't relate to the politics of a single one single nation on its own. It's really hard to get people excited about point five of a degree centigrade average, that there was a massive failure of science and of advice, because it couldn't bridge the gap between the global dystopic story and the kind of information and insight and anticipations that were needed to translate that into action at a level that could act: which is countries and regions and cities. And that transition is hugely happening and has happened towards these multiple stories, multiple models about what to do. I think we've now, I mean, like Sarah was saying, there's a massive untapped resource now of listening to stories that already exist, particularly those which aren't perhaps so mainstream, that already incorporates all sorts of insights of models of perspectives, and have already created networks of potential action that can make a difference in the next few years, which is exactly when we need them.

Peter Hayward

Zia Sardar and his colleagues at Postnormal Futures, and one of the things that Zia said was, along with the rise in broader knowledge and communication has also been the rise in ignorance, both willful and just the nature of not knowing. And we've seen particularly through the COVID time, the entire Trump presidency, this notion of fake news, and now the rise of conspiracy theories. Has that kind of played a role? Are you surprised by that? Or, in fact, do you expect to see that and see more of it?

Claire Craig

Well, part of it is back to this, we're trying to reclaim some power against the seductive nature of stories. I mean, stories are wonderful, yeah. But they can almost sweep away all kind of rationality as you go with them. So part of what we're trying to do is build tools or Bulwark things to use to combat false implausible, harmful stories. But also perhaps to help understand, because I mean, certainly, I've done quite a lot of public dialogue in science advice and in futures. And people are always thoughtful, they may be thinking in ways that you don't agree with and may seem ludicrous given what you yourself might know. But they're never completely irrational or stupid, within their own terms. So having a degree of respect, even for people who believe things that you might believe are ridiculous is not a good starting point. But understanding why we might be taking that point of view is usually a better way to proceed, as it were – better in the sense of more likely to be productive.

Sarah Dillon

It's a really important point to make, because, you know, someone could turn around to us and say: this is really dangerous – what you're doing because you're trying to make us take stories seriously, at a time when Trump is trying to get people to take stories seriously. And what we're doing is very much not the same as that. What we're trying to do is empower people to understand how and when a story is working in – we can be very reductive – a positive or evidentiary way and how and when it's not. So that is kind of for the story imbiber. But for the story listener, the person surveying the landscape, conspiracy theory is a very interesting example of a narrative network. It's a very interesting example of the way in which story listening, taking that story. And it's sharing, not the content of the story. But the sharing of the story seriously, can give decision makers really important and helpful information about the kinds of publics that they're engaging with, and how to engage with them. So I have a wonderful PhD student working on conspiracy theory at the moment. And if you look at some conspiracy theories, they're very much shared amongst, for instance, groups of people who feel disenfranchised by or distrustful of centres of power, and it might coalesce publics that aren't organized in orthodox terms, for instance, along the lines of age, or gender, or nationality. By taking stories seriously, it doesn't mean believing every story that's told is true; it means recognizing that they have powerful cognitive and affective functions in the world. And that if you start to map and trace and understand those, you can make better decisions in relation to, for instance, the kinds of publics that you're engaging with and the way in which you might want to help them understand stories and the world.

Claire Craig

Another thing that perhaps we haven't said clearly enough is that, in the practical implications of what we're talking about here, we're front and centre about plurality of evidence base. So we're never saying, listen to the story and take a take a view on the basis of that, but use it as one of many forms of evidence. So if there's evidence that vaccines are helpful and not harmful, from clinical trials, that is a jolly good and important thing. You can use your thinking about the stories alongside of all these other forms of evidence, which are also important.

Can I just go back for a moment to – I was talking about the kind of the shift in thinking about climate change from the big global models and global stories to the kind of more local. And I just thought, we have a couple of examples in the book, which may be illustrated, although Sarah can put it better than me, I'm sure. One of them is Zeitoun by David Eggers, which is an account of a man's experience during flooding in New Orleans. It connects a set of identities: he's a business person, a family man, he ends up being falsely accused of terrorism, because if it has ethnic origins. It shows the different groups, different networks, different collective identities, during the course of an extreme weather event, and it's that kind of connectedness that helps to complement you know, whether the water rose by a metre or a metre and a half, you know, and whether the net damage was x billion or y billion, and to think differently, perhaps about how you then might mobilize people in the future to work to rebuild differently in a particular area. Or there's an earlier novel Flight Behavior by Barbara Kingsolver, which is really thoughtful about how scientists and people living in a relatively poor area of the US who are the site of scientific exploration in this case, it's about butterflies and migration patterns that are being damaged by climate change. It's modeling the relationships between scientists and people living in a particular locality, in a really thoughtful way that would actually, I think, have helped many of the scientists – or could help – to think differently about how they then go about their business. So I just wanted to give a couple of examples.

Sarah Dillon

Yeah, no, they're great examples. And you're absolutely right, Claire, to stress the but what we call a pluralistic evidence base, a kind of ecosystem of knowledge and evidence, where you're judging on using stories in relation to and alongside other forms of evidence, including the scientific. So this is not at all a project that is intended to devalue the scientific. Absolutely not. It's just meant to recognize that there are other forms of knowledge that can compliment and strengthen and form part of a pluralistic evidence base that can inform decision making.

Peter Hayward

Thank you.

Fourth question is the communication question. I'm very interested as to how you designed and implemented and learnt how to communicate this to people who possibly didn't understand what it was you actually were writing about or why.

Claire Craig

Time will tell, won't it?

Sarah Dillon

I'm smiling at the past tense, which is the assumption that we figured out how to do that. I think it should be very much in the present.

Claire Craig

What we do argue for though, and you can see beginning to happen in some ways, but we would like to happen a lot faster is actual changes to the systems that enable new ways of thinking to happen. So futures, the systems that do futures work in the world at the moment, and the systems that provide advice at local or national city or global level. There are big systems in play, particularly for the sciences. You've got the IPCC to take an obvious example. We looked at the 1.5 degrees special report, and it had no humanities authors out of 279. Some of them were counted twice because they count by chapter, you could actually make some structural changes to things like that, or in the UK, the science advisory group in emergencies, SAGE, which is pivotal to emergency advice. You can make structural changes to say, right, we've got an emergency or we've got a very long term massive problem like the IPCC, what do we do now that incorporate storylistening and new forms of evidence? Because it is the case that the forms of evidence we've got are fantastic but they're not sufficient. So changing advisory systems. There are all sorts of ways in which evidence is synthesized now for public use, incorporating storytelling into that. So we've got sort of some systemic suggestions. But we're still practicing actually explaining what it means in conversations like this.

Sarah Dillon

Well, but Claire's given a wonderful what in my world would be called a performative answer, which does it rather than describes it, which is the performative answer in relation to practitioners is not so much this is the theory, but these are the things you can do to change to make changes that we think would be positive or beneficial. And what that performative answer shows, if I could then do the meta bit, is what I call, in other work, lexical flexibility. So you have to be – and, I think, actually, Pupul talked about this as well, you have to be able to describe what you do differently depending on who you're describing it to. So for practitioners, for policymakers, you have to give them the things that they can do. If, for me, maybe persuading humanities people, different kinds of arguments about the history of the value of the humanities, skepticism in the humanities about collaboration, about function, as in some way going to devalue the academic freedom or what we do. So to come back to the, I guess, theme of your podcast is, it's telling a different story, or framing things differently, depending on who you're speaking to, so that they can more easily take from what you're saying what's pertinent and relevant to them.

Peter Hayward

What's been the initial responses that you've noted? Because clearly, this is while the book is still to come, so to speak, or very, very close to coming. But clearly, people are already engaging with the idea.

Sarah Dillon

Very pleased that it's been very positive. So far, a common pattern of response is: this fills a gap. This provides a way of thinking and tools for thinking that we have all wanted but we haven't had and is going to then enable us to do the things that we want to do. And that 'us' is from the scientists and geographers working in climate science, to Rachel Adams is wonderful friend of mine in South Africa, who's working with the Social Science Research Council there and trying to incorporate local knowledges into decision making there. So a positive response. We should be honest and say it's we did circulate the book for quite extensive peer review, because it's so inter-sector and interdisciplinary. And we got some robust and very helpful responses there, which have helped us very much shore up things like what we've already talked about how we're what we're doing is different to the arguments circulating around fake news and Post truth how what we're doing is not intended to decenter or de-privilege scientific evidence and scientific knowledge. So that was really helpful in enabling us to clarify some of the perhaps slightly more controversial, contentious elements of the book's arguments.

Peter Hayward

Let's close with talking about the book. Tell us a bit about when people are going to start seeing it, and also what is going to accompany the book, because I can't imagine it's just going to be a case of, oh the book's published, we're finished, I would have imagined there are things you are going to do to encourage its take up and exploration,

Claire Craig

I don't think we've discussed this in quite the way that you're asking the question. So it's very helpful. I mean, first of all, we're concentrating on creating different accounts, as Sarah said, and because we have been so determined that it should be rigorous and not least because it's quite threatening, potentially, or it seemed to be received as threatening from time to time – that we were kind of going to try to knock down the whole scientific edifice.

Sarah Dillon

Yeah.

Claire Craig

And also that we were telling humanities scholars that they couldn't carry on being independent of government. Neither of which is true at all. So we're focusing on giving shorter accounts aimed at practitioners, people working on the advisory interface with governments or with cities, or with global bodies. With researchers in particular different areas, there's massive scope for new research questions, but actually historical questions: how can we look back, as you were suggesting, but look back even just to the 20th century, and learn more about how stories have created the kind of models or points of view that have shifted public debates, and what would that tell us. There's a massive set of opportunities for what I would call innovative practice. So, you know, let's get some bits of experimentation. I'm just now working with the International Network for Government Science Advice, and they're really grappling, one of the key learnings so far from the pandemic is this need to have multidisciplinary evidence better and more rapidly accessible. Epidemiology is essential, but it's not sufficient. So I'm hoping at least to begin to work with some innovative practitioners on actually applying this, building in ways to apply it, and then learn from that practice. And as Sarah mentioned, there are some examples of that happening already. So it may be Sarah and I's slightly different natural orientations will show themselves. I'm thinking, how can we use this in some practice? And you're perhaps thinking already about the next kind of research questions? I don't know.

Sarah Dillon

Both/and – and that's one of the the refains of the book is both/and not either/or. We've added at the end of our website on the contact page that we're really interested to do more work – you're absolutely right, Peter, the book isn't the end. It sounds very corny, but it's hopefully the beginning. We invite people to get in touch with us who are excited and inspired or who find deeply useful the ideas that they've come across, so that we could have any number of spin outs and connected projects – be they practical ones or research ones. So you know, we invite listeners, if you're interested, get in touch with us. We welcome working with people, because of course, we don't have the expertise across everywhere that this might be applicable. So we're always happy to learn and collaborate. I guess, as an individual, as a literary scholar, I'm writing other academic papers about what I'm calling functional criticism. So changing or thinking about – not changing – adding to the where, the what, and the why, and the how humanities scholars do what they do. And each of those changes to the where, the what, the why, and the how might affect methods, might affect language, might affect communication, whilst still preserving the skills and the methods of analysis and engagement that that make our disciplines what they are. So there's a sort of internal academic thread ongoing from this, which is perhaps – and this is why I'm hesitating about going into more detail – because probably not very interesting or of relevance to some of your listeners. So again, it's about which story do we tell? And I think that the practitioner story is the one that might be most interesting to your listeners.

Claire Craig

And Sarah, you along the way though you have already done things like your work on autonomous flight – haven't you? On anticipation?

Sarah Dillon

Oh, thank you! I'd forgotten about that. Yeah, I think one of the other things that I'm trying to do in my own work is to put into practice some of the things that I've learned from the wonderful engagements I've had with people in Future Studies. So I did a project with a great postdoc called Olivia Belton, which was to some extent inspired by Stuart Candy's work and 'The Thing from The Future' and his uses of games, which I came across in in Riel's collection. And so we – well, Olivia, I should give her the credit – designed a storytelling game that we use, then to start to investigate anticipatory assumptions about the future of autonomous flight. And that paper came out in Futures late 2020, early 2021. So I'm also – and I guess that's changing that the how of what literary studies does: what would it mean to bring in different methods into literary studies, and use, combine our skills with those methods in order to do perhaps futures-type work, but in a slightly different context? So I'm always interested to play and experiment with different ways of doing things. And I'm learning a lot from the knowledge that I've gained over the last year from teachers, practitioners within and outside of the academy.

Claire Craig

And we should say that the book has its own website, where we're putting the things that we do or links to them, as we do them.

Peter Hayward

Excellent.

Sarah Dillon

Yeah. And also trying to do them in different formats. Trying to do things that people can read things that people can watch. We were about to put things that people can listen to, and then realized we couldn't use 'listen', because it's such an important word in the book. So we've got a 'hear' section, h-e-a-r, of the website, which sounds a little off, but it's one of the senses in which when you start to create a new framework, you start to create a new language. And so we have a massive and very important glossary at the back of the book, which Claire was very insistent from the beginning that we had, and I sort of let her get on with it. And by the time we got to the end, I was like, thank you so much for making sure that we had this, because of course different words – and especially in future studies, which is still as you say, a discipline that's evolving and in flux – different words mean different things to different people, the same word means different things to different people. So we've tried to pin down our language a little bit and pinning down exactly what 'listen' means in our context has been one of the one of the things that we've had to do.

Peter Hayward

Great. On behalf of the Futurepod community, I'd like to congratulate you on the book, for a start, and I really encourage the Futurepod community to engage with the book, take it up with their respective associations and federations to discuss it. It sounds like a very, very valuable contribution to the field, but to you two, thank you for taking some time out of your busy days to talk to the Futurepod community.

Claire Craig

Thank you. It's been a great pleasure.

Sarah Dillon

Yeah, and an absolute honor to be included with them, amongst all the other wonderful people that you've spoken to. We've learned a lot from listening to the podcast, so thank you.

Peter Hayward

This has been another production from Futurepod. Futurepod is a not for profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support Futurepod, go to the Patreon link on our website. Thank you for listening. Remember to follow us on Instagram and Facebook. This is Peter Hayward saying goodbye for now.